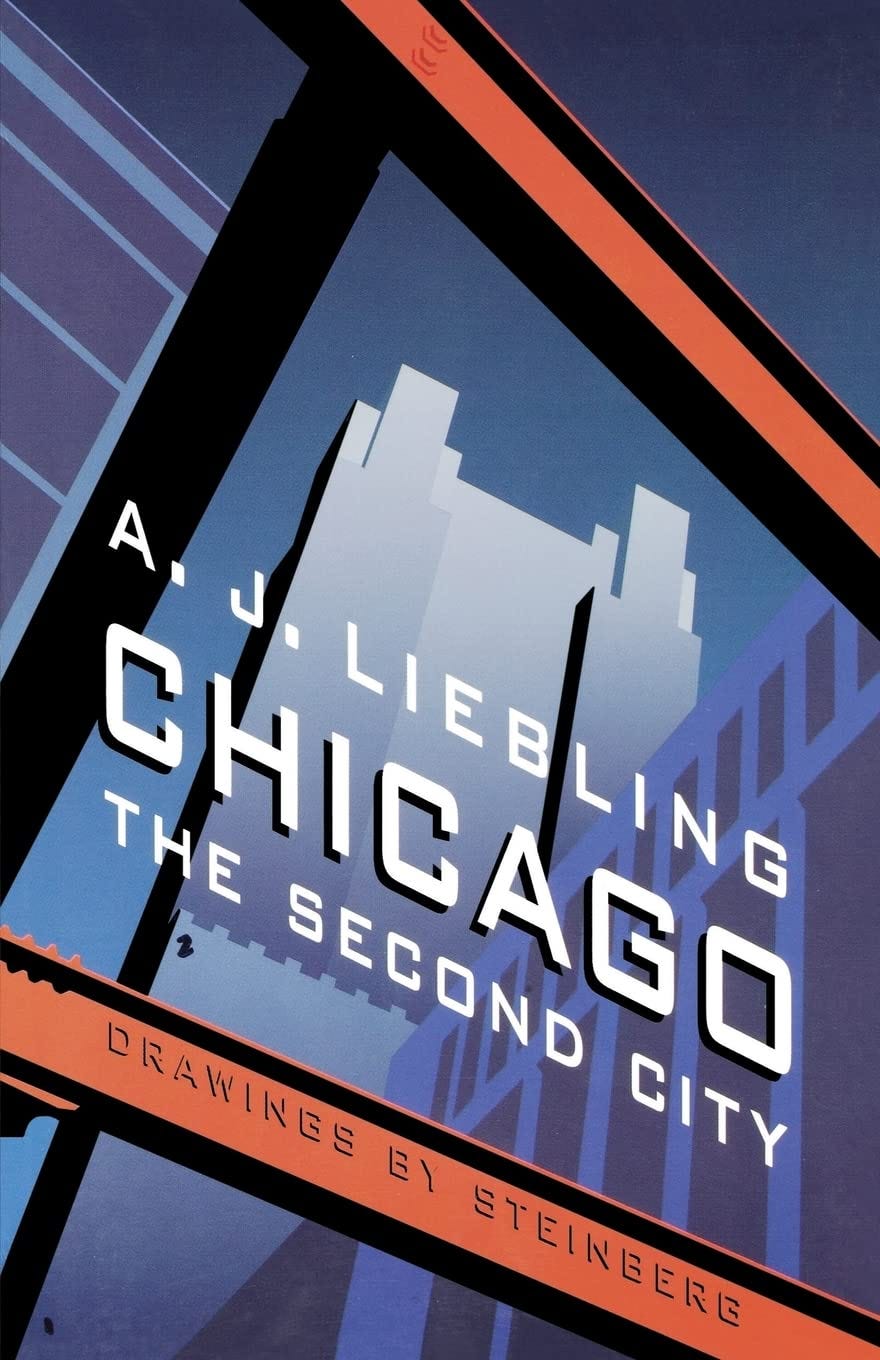

A. J. Liebling, Chicago: The Second City (1952)

When a New Yorker correspondent profiled the postwar "not-quite-metropolis," not every Chicagoan was pleased

You've almost certainly seen Saul Steinberg's 1976 New Yorker cover illustration View of the World from 9th Avenue, whether or not you read the New Yorker — and indeed, whether or not you were alive in 1976. Lower Manhattan dominates the image; beyond the Hudson river, all dissolves into near-abstraction, labeled only by a handful of city, state, or country names. These are rendered in upper-case letters with the curious exception of Chicago, off by itself in a featureless corner of the patch of green meant to represent the rest of the United States of America. On the cover of the New Yorker, such an image reads as self-deprecating. (Or rather, it would read as self-deprecating if it didn't also transmit the assumption that the skewed perceptions it satirized are, on some level, justified.) When an earlier version of the same concept, which seems directly to have inspired Steinberg's rendition, appeared in the Chicago Tribune in 1922, it must have come off as more resentful. But then, it could also have been drawn in the spirit of bullishness, given that Chicago in the nineteen-twenties seemed poised to overtake New York as the dominant city of the U.S.

By the end of the forties, when the New Yorker's A. J. Liebling spent a year in Chicago, those days were over. The question of what put an end to them drives the series of articles he published in the magazine, then in book form, in 1952. The slim Chicago: The Second City is somewhat filled out by an introduction and footnotes concerned almost entirely with the reactions the original pieces drew from Chicagoans. "The letters from the visitors, and from expatriates, were almost all favorable," Liebling writes, while "those from people who were still there weren’t. The most catamountainous of all came from the suburbs; the people who wouldn’t live in the city if you gave them the place rose to its defense like fighters off peripheral air-fields in the Ruhr in 1944." Certain of the responses quoted at length exhibit the kind of articulate quasi-literacy I associate with the early twentieth century. "Is Mr. Liebling forming a 'Be Nasty to Chicago Club'???" asks one. Or perhaps he's unwittingly "endeavoring to inspire helpful people to action at the Chicago front," in which case "I should adore to board the next plane possible and be first in line to tenderly and encouragingly grasp the hand of Mr. Liebling as he staggers (I hope) backward from reading such reactionaries as this one of many of which he must be in recipience daily!"