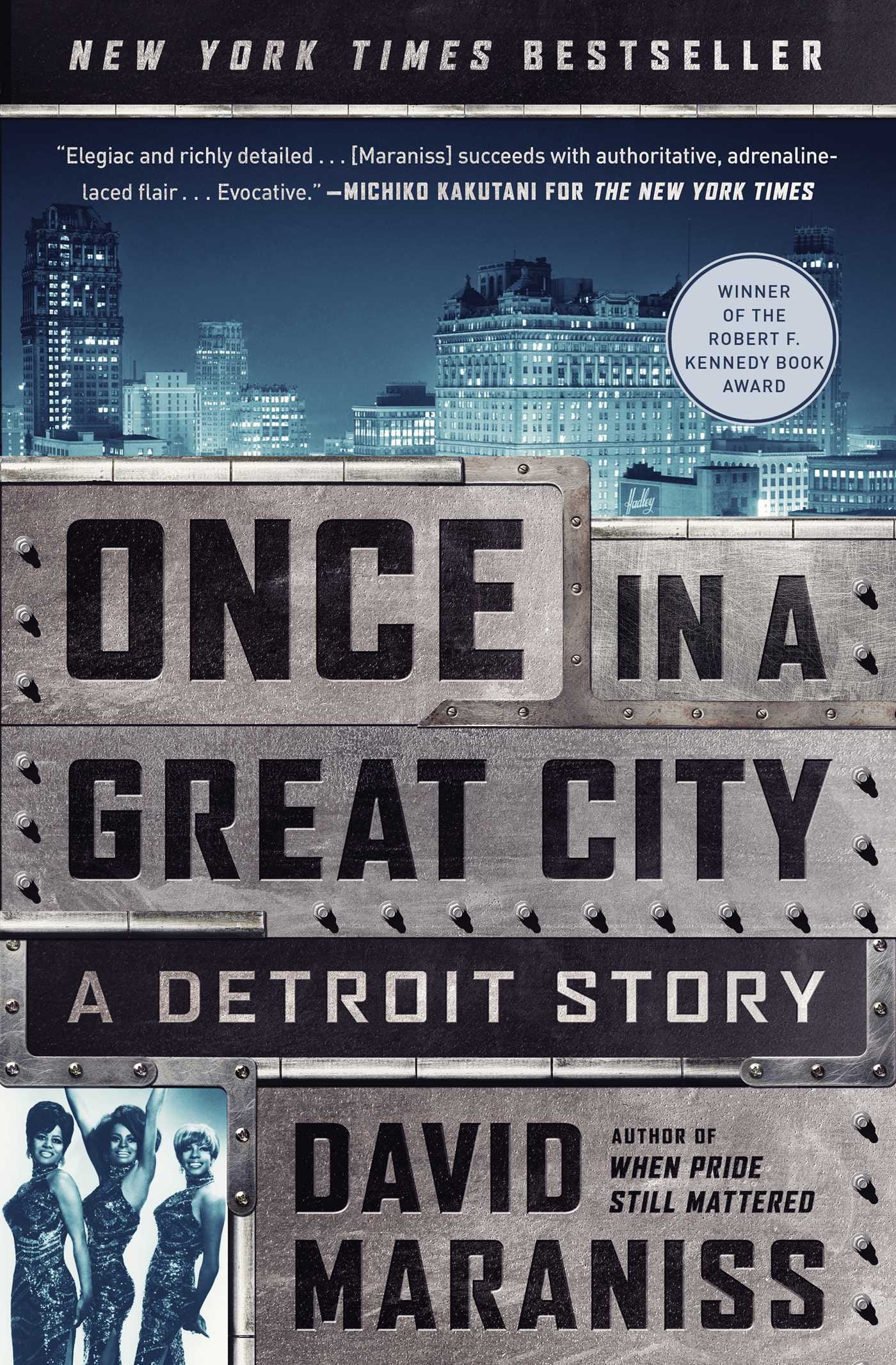

David Maraniss, Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story (2015)

Writers tend to obsess over Detroit's decline, but David Maraniss focuses instead on the city's last glory days in the early 1960s, the time of Motown, the Mustang, and MLK

The twenty-tens brought forth a spate of books about Detroit, each of which takes a different angle on that troubled city: the straightforward history of Scott Martelle's Detroit: A Biography, the bleak reportorial machismo of Charlie LeDuff's Detroit: An American Autopsy, returned Detroiter Marc Binelli's Detroit City Is the Place to Be: The Afterlife of an American Metropolis, new arrival Drew Philp's A $500 House in Detroit: Rebuilding an Abandoned Home and an American City. In the middle of all of these, in more than one sense, we have journalist David Maraniss' Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story. Though born in Detroit, Maraniss didn't come of age there, nor did he return to live there in adulthood, but in light of his career-long focus on twentieth-century American history, it isn't hard to understand why he would regard it as a promising subject.

To tell the story of Detroit, Maraniss writes in an "author's note" before the main text, "I chose to go back not to the fifties, when my family lived there, but once again to the sixties, a decade I’ve explored in various ways in many of my books" (not least They Marched into Sunlight, which is about the Vietnam War and its protestors). He then gets even more explicit about the parameters of his project, explaining that its chronology "covers eighteen months, from the fall of 1962 to the spring of 1964. Cars were selling at a record pace. Motown was rocking. Labor was strong. People were marching for freedom. The president was calling Detroit a 'herald of hope.' It was a time of uncommon possibility and freedom when Detroit created wondrous and lasting things."

That this book focuses on Detroit in its glory days rather than the prolonged decline that has followed them could come off as either deeply earnest or faintly ironic, though Maraniss hardly seems like the ironic type. Not that he always leaves the contrast between the city as it was in the early sixties and what it became thereafter as an exercise for the reader, nor even implies that it went unforeseen in Detroit at the time. A few chapters in, he cites an obscure 1963 report by Wayne State University's Institute for Regional and Urban Studies that forecast a fall in the city's population from 1,670,144 in 1960 (the figure found by that year's U.S. Census) to 1,259,515 by 1970. Even at the time of publication, the researchers explained, "productive persons who pay taxes are moving out of the city, leaving behind the non-productive."