Joan Didion, Miami (1987)

The late Slouching Towards Bethlehem author reports from less a "wicked pastel boomtown" than a bitter and paranoid tropical fever dream

Joan Didion is associated with no place more than southern California. Yet she also spent two major stretches of her life in New York, one from the mid-nineteen-fifties to the mid-nineteen-sixties, and another from 1988 until her death this past December. She made that second move the year after publishing Miami, an ostensible examination of the titular South Floridian metropolis mainly, she later admitted, "about what I think is wrong with Washington.'' Yet Miami is also about a specific Miami, and in a sense the dominant one: Cuban Miami, whose inhabitants constituted 56 percent of the total population by the time Didion began visiting the city in the mid-eighties. "There had come to exist in South Florida two parallel cultures," she writes, "separate but not exactly equal, a key distinction being that only one of the two, the Cuban, exhibited even a remote interest in the activities of the other."

What surprises me about this is the implied existence of a non-Cuban Miami. Though I still haven't been there, I've long imagined the city's overall cultural formation as even more dependent on Cuba than that of Los Angeles has been on Mexico. Of course, even 35 years ago a major American city's being influenced by a large number of Latin American immigrants wasn't a novelty. Miami’s uniqueness manifests to Didion linguistically: "In, say, Los Angeles, Spanish remained a language only barely registered by the Anglo population, part of the ambient noise, the language spoken by the people who worked in the car wash and came to trim the trees and cleared the tables in restaurants. In Miami Spanish was spoken by the people who ate in the restaurants, the people who owned the cars and the trees, which made, on the socioauditory scale, a considerable difference."

Hence the way I occasionally heard Spanish described by my fellow students of the language back in Los Angeles: there an advantage, but in Miami a necessity. Though evidently without Spanish herself, Didion was sensitive enough to the undercurrents of power to pick up on what its use revealed about the city. (The Hispanophone David Rieff published his own Going to Miami in 1988, followed by Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World in 1991, but neither book remains prominent in the literature of those cities.) She engages Cuban Miami through its English-speakers, as when "on one of the first evenings I spent in Miami I sat at midnight over carne con papas in an art-filled condominium in one of the Arquitectonica buildings on Brickell Avenue and listened to several exiles talk about the relationship of what was said in Washington to what was done in Miami."

All well-educated, these exiles are also "well-read, well-traveled, comfortable citizens of a larger world than that of either Miami or Washington, with well-cut blazers and French dresses and interests in New York and Madrid and Mexico. Yet what was said that evening in the expensive condominium overlooking Biscayne Bay proceeded from an almost primitive helplessness, a regressive fury at having been, as these exiles saw it, repeatedly used and repeatedly betrayed by the government of the United States." In its diagnostic incisiveness and near-affectless delivery, this passage reads to me like vintage Didion. But its scene has stuck more vividly with me than any other in the book for more reasons than that. The mention of the firm Arquitectonica, for example, should get the attention of every enthusiast of American architecture in the nineteen-eighties — or for that matter, of American popular culture in the nineteen-eighties.

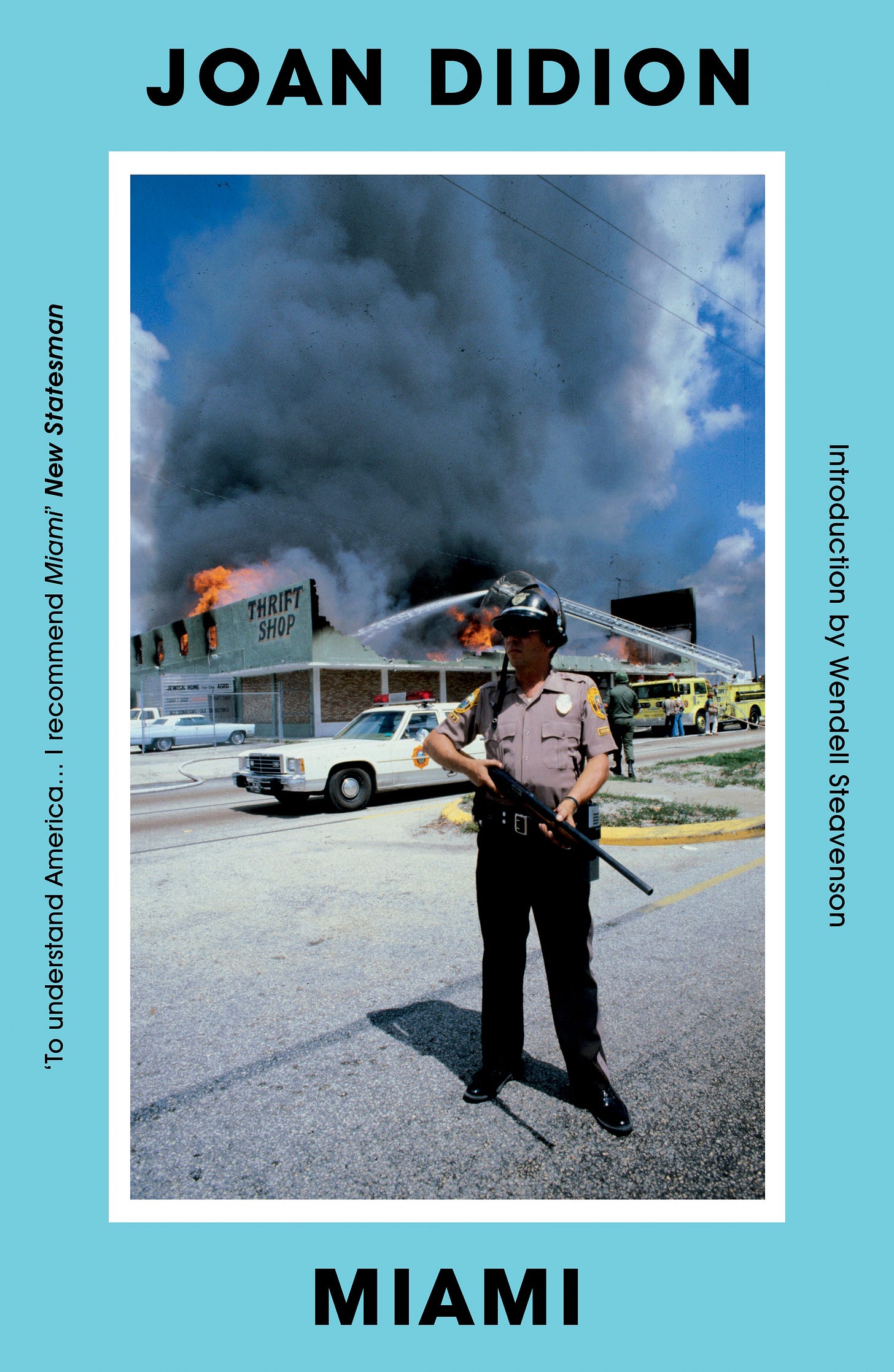

Arquitectonica "produced the celebrated glass condominium on Brickell Avenue with the fifty-foot cube cut from its center, the frequently photographed 'sky patio' in which there floated a palm tree, a Jacuzzi, and a lipstick-red spiral staircase." Now known as Atlantis on Brickell, that fabulously dated building appeared prominently in the opening-credits sequence of Miami Vice, a series Didion describes as having painted Miami as "a rich and wicked pastel boomtown," though the real place strikes her more as another "spectacularly depressed" southern city. She finds a clearer socio-architectural metaphor in the Omni International, "a hotel from which it was possible to see, in the Third World Way, both the slums of Overtown and those island houses with the Unusual Security and Ready Access to the Ocean." The Cubans made good dance in the Omni's inaccessible ballroom levels, visible to the harder-up demographic groups passing through the mall below.

In this tableau Didion identifies "the most theatrical possible illustration of how a native proletariat can be left behind in a city open to the convulsions of the Third World, something which had happened in the United States first and most dramatically in Miami but had been happening since in other parts of the country." The existing working-class population, in other words, had been economically displaced by new, large, unexpected, and in large part overqualified waves of immigration; "Black Miami had of course been particularly unprepared to have the world move in." The first time I read the words "the world moved in" they were about Los Angeles, and they seemed to me an apt summation of what had happened there since the 1960s. The resulting grievances are reflected by any number of Los Angeles movies, and even more so by events like the riots of 1965 and 1992.

Miami has endured riots of its own, first during the 1968 Republican National Convention and then three times in the nineteen-eighties. The first and deadliest of the latter broke out in 1980, during the time of the so-called Mariel boatlift that would eventually bring about 125,000 Cubans to Florida. To Miami's Cubans "Mariel appeared as a betrayal on the part of yet another administration," Didion writes, "a deal with Fidel Castro, a decision by the Carter people to preserve the status quo in Cuba by siphoning off the momentum of what could have been, in the dreamtime of el exilio, where the betrayal which began with the Kennedy administration continued to the day at hand." It was the Kennedy administration, of course, that organized and disavowed 1962's ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion, which ended with the secretly trained men of the 2506 Brigade dead or captured in Cuba.

"In many ways the Bay of Pigs continued to offer Miami an ideal narrative, one in which the men of the 2506 were forever the valiant and betrayed and the United States was forever the seducer and betrayer and the blood of los martires remained forever fresh,'' Didion writes. By the eighties, the exiles hoped less that Castro could actually be overthrown than that the Nicaraguan contras would ''not be treated by the Reagan administration as the men of the 2506 had been treated, or believed that they had been treated, by the Kennedy administration.'' Didion was well placed to consider such grim and bewildering Latin American proxy wars, her previous nonfiction book having been about American involvement in El Salvador. Both it and Miami began as multi-part journalistic pieces for the New York Review of Books, though in Didion's depiction Miami itself scarcely admits of any traditional journalistic methods.

But then, Didion wasn't a traditional journalist. Indeed, not being one seems a requirement for understanding Miami, which she calls "not exactly an American city as American cities have until recently been understood but a tropical capital: long on rumor, short on memory, overbuilt on the chimera of runaway money and referring not to New York or Boston or Los Angeles or Atlanta but to Caracas and Mexico, to Havana and to Bogotá and to Paris and Madrid." With the passage of time (and lack of regime change in Cuba), relations between el exilio and the relevant governments had grown more complex, and relations among the exiles themselves often turned violent. In the seventies and eighties the car bomb seems to have been the method of choice for dispatching one's political enemies, underscoring one aspect of Miami's foreignness: unlike in the rest of late-twentieth-century America, politics was still happening there.

Miami, Didion writes, was "the only American city I had ever visited in which it was not unusual to hear one citizen describe the position of another as 'Falangist,' or as 'essentially Nasserite.'" Such citizens are all, of course, members of el exilio, and their "urge toward the staking out of increasingly recondite positions, traditional to exile life in Europe and in Latin America, remained, in South Florida, exotic, a nervous urban brilliance not entirely apprehended by local Anglos, who continued to think of exiles as occupying a fixed place on the political spectrum, one usually described as 'right-wing,' or 'ultra-conservative.'" Such clumsy ideological approximation is characteristic, in Didion's view, of the broader misperception through which "Anglos (who were, significantly, referred to within the Cuban community as 'Americans') spoke of cross-culturalization, and of what they believed to be a meaningful second-generation preference for hamburgers, and rock and roll."

Yet "fixed as they were on this image of the melting pot, of immigrants fleeing a disruptive revolution to find a place in the American sun, Anglos did not on the whole understand that assimilation would be considered by most Cubans a doubtful goal at best." For the most part, Miami Cubans exhibited little interest in "becoming American" in the manner of early-twentieth-century Ellis Islanders. Thus, as their numbers in the city increased, so a greater and greater cultural distance separated the city itself from the rest of the U.S. The increasing dominance of the Spanish language was obvious; more subtle was that of "a view of politics as so central to the human condition that there may be no applicable words in the political vocabulary of most Americans," who had grown dully unresponsive to practically everything but real-estate values, gas prices, and the occasional crime wave.

By the eighties, this ideological tropicalization had turned Miami into a schizophrenic's delight, imbued with a paranoid ambience and shot through with ambiguous but nonetheless startling interconnections. Thus the city made for Didion an ideal subject, given her much-celebrated ability to not just pick up on a vibe but articulate it. Though not one of her best-known works, Miami represents a moment of neat alignment between the nature of her material and the tendency of her prose toward intuition, implication, and incantation:

Miami stories were low, and lurid, and so radically reliant on the inductive leap that they tended to attract advocates of an ideological or a paranoid bent, which was another reason they remained, for many people, easy to dismiss. Stories like these had been told to the Warren Commission in 1964, but many people had preferred to discuss what was then called the climate of violence, and the healing process. Stories like these had been told during the Watergate investigations in 1974, but the President had resigned, enabling the healing process, it was again said, to begin. Stories like these had been told to the Church committee in 1975 and 1976, and to the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1977 and 1978, but many people had preferred to focus instead on the constitutional questions raised, not on the hypodermic syringe containing Black Leaf 40 with which the CIA was trying in November of 1963 to get Fidel Castro assassinated, not on Johnny Roselli in the oil drum in Biscayne Bay, not on that motel room in Dallas where Marita Lorenz claimed she had seen the rifles and the scopes and Frank Sturgis and Orlando Bosch and Jack Ruby and the Novo brothers, but on the separation of powers, and the proper role of congressional oversight.

On balance this is more of a book about politics than a book about urban life, and in its more intensely political passages its rhetoric turns near-parodically Didionesque. "Midway through the Reagan administration, it was taken for granted that the White House schedule should be keyed to the daily network feeds," she writes. "It was taken for granted that the efforts of the White House staff should be directed toward the setting of interesting scenes. It was taken for granted that the overriding preoccupation of the White House staff" should be "the invention of what had come to be called 'talking points,' the production of 'guidance,'" and "the creation and strategic management" of what White House communications director David Gergen calls "the story line we are trying to develop that week or that month." And

It was taken for granted, above all, that the reporters and camera operators and still photographers and sound technicians and lighting technicians and producers and electricians and on-camera correspondents showed up at the White House because the President did, and it was also taken for granted, the more innovative construction, that the President showed up at the White House because the reporters and camera operators and still photographers and sound technicians and lighting technicians and producers and electricians and on-camera correspondents did.

For all its portentousness, and despite its virtuosity, this passage doesn't quite land today. American politics, especially presidential politics, has been so long regarded (or at least accepted) as a media enterprise on par with professional wrestling that I can't imagine how deeply readers would have been disturbed by it even in 1987, nearly two decades after The Selling of the President 1968. Even among Cuban exiles, Didion finds current the belief that for the United States government, other parts of the world "existed only as 'issues.' In some seasons, during some administrations and in the course of some campaigns, Central America" — and in earlier times, Cuba — "had seemed a useful issue, one to which 'focus' and 'attention' could profitably be drawn. In other seasons it had seemed a 'negative' issue, one which failed to meet, for whatever reason, the test of 'looking good.'"

Didion's distinctiveness has received fresh examination in the months following her death. By way of an obituary, the Atlantic contributor Caitlin Flanagan re-posted a not-entirely-laudatory piece on Didion's work published a decade ago, in which she makes a point about it often presupposed but seldom explicitly argued. She quotes from a panel discussion two of whose participants, female, attempt to convince a dubious third, male, of Didion's literary greatness. Enthusiastically they adduce such allegedly immortal details from Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album as "the smell of jasmine" and "the list she put on her suitcase before she left," whose significance nevertheless remains as obscure to the male panelist as it does to me. "To really love Joan Didion," Flanagan writes — "to have been blown over by things like the smell of jasmine and the packing list she kept by her suitcase — you have to be female."

In Miami, Didon's female gaze does register details that a man would miss. "The entire tone of the city, the way people looked and talked and met one another, was Cuban," she writes. Its women have "a definable Havana look, a more distinct emphasis on the hips and décolletage, more black, more veiling, a generalized flirtatiousness of style not then current in American cities." She notes that a group of society ladies "wore Bruno Magli pumps, and silk and linen dresses of considerable expense. There seemed to be a preference for strictest gray or black, but the effect remained lush, tropical, like a room full of perfectly groomed mangoes." In that Arquitectonica building she dines with "a quite beautiful young woman in a white jersey dress, a lawyer, active in Democratic politics in Miami," whose twice-referenced crushing of a cigarette Didion freights with a meaning I have yet to decipher.

Still, the image isn't without allure. Though lighting up after dinner, especially in a private home, was hardly uncommon in the mid-eighties, the very notion now evokes a a civilization lost across much of the urban world. In Didion's rendering, Miami seems to have kept a healthy distance, as it were, from the diet-and-exercise compulsions that characterized middle-class American popular culture at the time. "In the shoe departments at Burdines and Jordan Marsh there were more platform soles than there might have been in another American city, and fewer displays of the running-shoe ethic," writes Didion, several of whose reports of place incorporate such department-store visits. The more I consider when I'll be able to visit Miami myself, the more fervent my hopes that the city has retained at least some qualities of the oblique, the fevered, the louche — has retained, in other words, its un-Americanness.

Under current mayor Francis X. Suarez (son of Xavier Suarez, mayor when Didion came to town) Miami has pushed to attract technology headquarters, especially of companies disaffected in Silicon Valley. It dismays a city-lover to see a metropolis with its own distinctive culture and atmosphere straining to imitate the likes of Sunnyvale and Palo Alto. But this may yet fail if conditions have remained as they were in the Miami Didion knew, where "a tropical entropy seemed to prevail, defeating grand schemes even as they were realized." Among those schemes she includes Metrorail, a transit system of similar vintage and stuntedness to the one now operating in her birthplace of Sacramento. Miami is Didion's only city book; despite issuing a good few meditations on her own California roots, she never devoted a full-length work of nonfiction to her hometown. If she had, you'd probably have just read about it.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His current projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.

What is your point here?

Hmmm