Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built (1994)

The Whole Earth Catalog creator explains why buildings should grow like cities

Stewart Brand isn't the first public intellectual one associates with cities. In fact, he's probably closer on the grand map of cultural phenomena to the rejection of cities, specifically the post-hippie ethos-impulse to go back to the land, albeit equipped with the highest possible technology. This owes, as anyone who's heard Brand's name understands, to his having founded the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968. As it happens, I wrote about that publication's online archive for Open Culture last year, and in so doing lost a fair few hours browsing its digitized issues. The sheer quantity of both curatorial attention and sheer information that went into them makes them into a kind of time machine. Not having been around to experience "the Sixties," however broadly defined, I felt as if, like Firesign Theatre albums, Whole Earth catalogs brought me as close as I'll ever get to doing so.

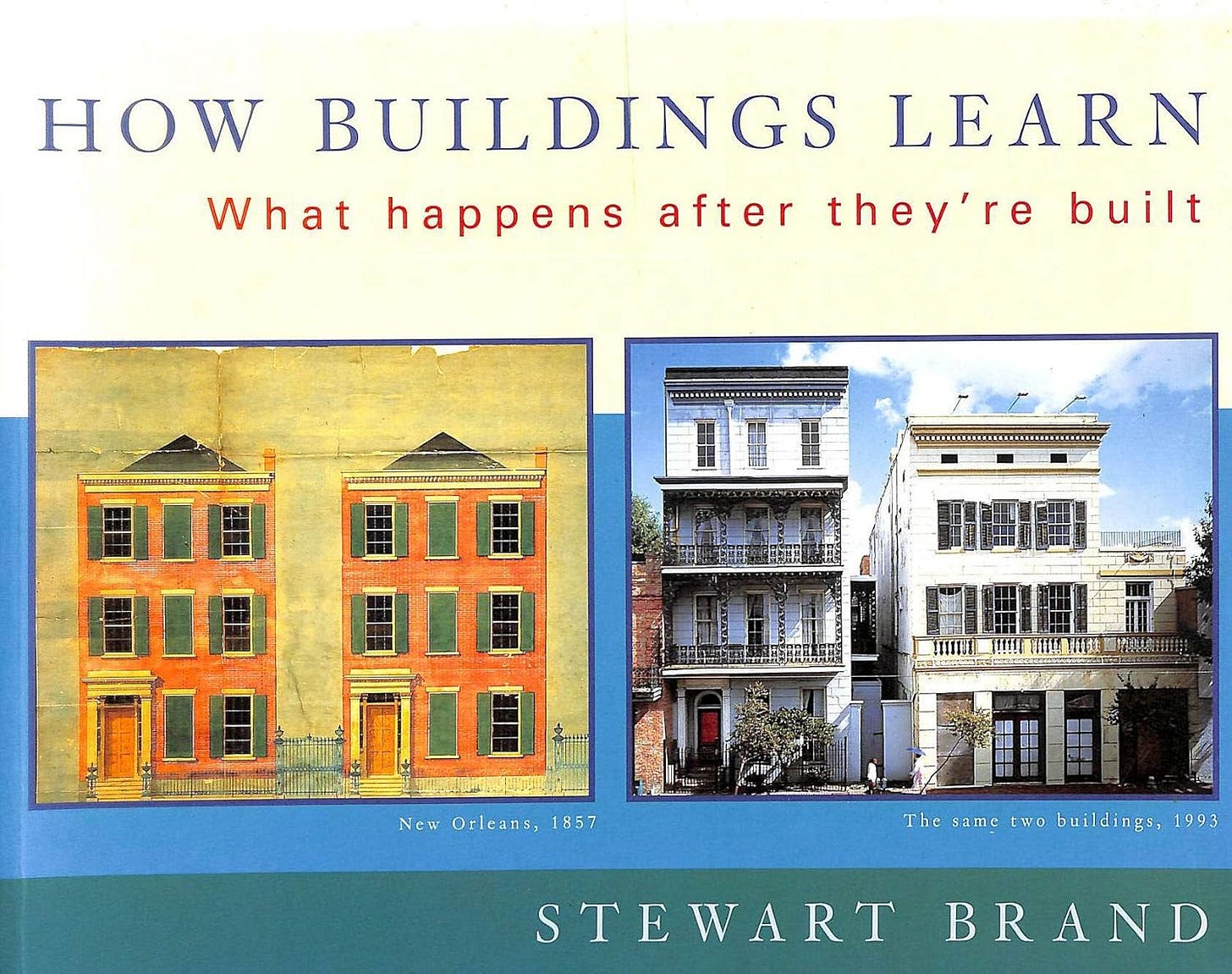

I was, however, around to experience the nineties, when the Zeitgeist turned Brand's way again. His long enthusiasm for the personal computer (a term said, incredibly, to be his own coinage) had been vindicated and then some by the wide adoption of the internet. But in a grander sense, the technologically astute West Coast bohemians of the sixties had, by that point, taken the helm of the culture, or at least risen to prominence within it. In 1996, when Brand and computer scientist Danny Hillis established the Long Now Foundation, with its 10,000-year clock, people took notice. Appreciative attention had also been paid, two years earlier, to Brand's book How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built, a title that piqued my curiosity every time I ran across it over the decades. Only now, thirty years after its publication, have I actually read it.

For several reasons, that delay was to the good. I now possess the "lived experience," as the kids say, of what thirty years feels like, and in How Buildings Learn, that practically constitutes a basic unit of time. I've also become organically familiar with the work of figures in Brand's cultural orbit: Brian Eno, for instance, over whose published diary A Year with Swollen Appendices I obsessed in high school even before having heard many of his albums. Brand is a major presence in A Year with Swollen Appendices, and Eno credits his e-mailed words of wisdom ("Why don't you assume you've written your book already — and all you have to do now is find it?") with getting him started writing it. Eno, in turn, was one of the "muses" Brand selected to preside over the project of How Buildings learn, alongside Hillis and an architect named William Rawn.

Had I also read How Buildings Learn back in high school, I wouldn't have been to practically any of the places where Brand finds examples of learning and non-learning buildings. (He does write about Sausalito, in northern California, where he lived while working on the book and seems to live still today. I spent a few childhood years just up the road, but if I ever set foot in Sausalito proper, it didn't make a lasting impression.) Nor would I have read any of the books he references, some of whom I've at this point reviewed here on Books on Cities: Brand claims that Joel Garreau's study of new-built exurbs Edge City "reveals more of present-day American reality than any other book I can think of," and he quotes heavily enough from conversations with A Pattern Language lead author Christopher Alexander to make him practically a collaborator on certain chapters.

Much like A Pattern Language, How Buildings Learn is a book primarily concerned not with cities but individual structures, which Brand groups into three broad categories. He enthuses over cheap "Low Road" buildings "that no one cares about" for the seemingly infinite opportunities for improvisatory renovation and customization they offer their occupants. Examples include MIT's Building 20, hastily put together during World War II as a "temporary" structure but ultimately extant for 55 intellectually and technologically productive years, and a considerably less-celebrated shipyard warehouse of similar vintage in which Brand's wife once ran "an equestrian mail order catalog business." Against Low Road buildings, by their nature "successively gutted and begun anew," Brand sets the "High Road" buildings that are "successively refined" over decades, even centuries: George Washington's Mount Vernon; Thomas Jefferson's Monticello; Chatsworth, the expansive seventeenth-century estate now in the possession of the (extensively quoted) Duchess of Devonshire.

Though Brand gives these two types of building a great deal of attention for the ways in which they change over time — how they "learn" — they together constitute only a small part of the built environment. "Most Buildings have neither High Road nor Low Road virtues," he writes. "The very worst are famous new buildings, would-be famous buildings, imitation famous buildings, and imitation imitation buildings." These inflexible "No Road" structures, in his view, suffer a kind of inflicted learning disability. Target number one of his criticism here is also located on the MIT campus: the I. M. Pei-designed Wiesner building, constructed in 1985 to house the MIT Media Lab (itself the subject of Brand's previous book), with its "vast, sterile atrium" that "cuts people off from each other," its interior concrete walls that make running cable difficult, and its classrooms prematurely optimized for technologies that never caught on.

Whatever its shortcomings as a research facility, the Weisner building also looks surprisingly banal for the work of the most famous architect in the world at the time. But Brand seems to have a bone to pick with starchitecture per se, objecting particularly (and startlingly, given what one would imagine as their similarly capacious human-oriented sensibility) to the work of Richard Rogers. In the case of Lloyd's Tower in London, also from 1985, "the vaunted adaptivity in the building was high-tech and at a grandiose scale, oblivious to the individual worker and workgroup"; exteriorizing its services "in order to open interiors for flexible space planning led to attractive but expensive exterior detailing and burdensome maintenance costs." Brand makes much of a survey that revealed that three-quarters of Lloyd's employees "preferred their former building," conducted though it was only three years after the company had moved into the new one.

Even when Brand was writing How Buildings Learn, Lloyd's Tower had stood for less than a decade, making it still practically fresh by London standards. Since fast-tracked to Grade I listing, it seems to have become a well-respected work of architecture, if not a particularly cheap one to keep up. Brand also takes to task the somewhat longer-established Centre Pompidou in Paris, which Rogers designed in collaboration with Renzo Piano and Gianfranco Franchini. Ostensibly designed "to accommodate all manner of change," this "spectacular inside-out arts complex" has nevertheless become "an exorbitant scandal of rust and peeling paint" that testifies to the folly of exposing services. Indeed, the whole building had to close down for more than two years of renovations soon thereafter, and I only got the chance to see it myself last year because another, four-year-long closure had been postponed due the upcoming Olympics.

I quite like the Pompidou, not least for the sharp contrast it makes with the practically frozen built environment of central Paris. (Then again, I appreciate the Tour Montparnasse for the same reason.) London, too, is to my mind a more interesting city for having Lloyd's Tower. Though Brand says nothing in How Buildings Learn about the Barbican, a favorite place of mine, I suspect he wouldn't love it; he makes reference throughout the book to what he sees as concrete's inflexibility and tendency toward unattractive aging, and at one point offhandedly describes Paul Rudolph's Yale Art and Architecture building as "infamously brutalist." Contrary to the miserable accounts so often cited about such buildings, part of me believes — no doubt irrationally — that, occupying a work of brutalism, I would feel feel not inconvenienced and depressed but satisfied, even ennobled.

"The destruction of brutalist buildings is more than the destruction of a particular mode of architecture," says the critic Jonathan Meades in his documentary Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry. "It's a form of censorship of the past, a discomfiting past, by the present. It’s the revenge of a mediocre age on an age of epic grandeur." Brutalism reminds us that "we don’t measure up against those who took risks, who flew and plunged to find new ways of doing things, who were not scared to experiment, who lived lives of perpetual inquiry." Meades' priorities apparently differ from those of Brand when the latter writes that "art flouts convention. Convention became conventional because it works. Aspiring to art means aspiring to a building that almost certainly cannot work, because the old good solutions are thrown away. The roof has a dramatic new look, and it leaks dramatically."

Leaky roofs come up again and again in How Buildings Learn, whether of James Stirling's Cambridge history-faculty building, Monticello, an ill-fated memorabilia warehouse in Emeryville, or every geodesic dome ever built. "As a major propagandist for Fuller domes in my Whole Earth catalogs," Brand writes, "I can report with mixed chagrin and glee that they were a massive, total failure." For the older, wiser Brand, these domes stand (such as they've managed to) as evidence of the superiority of what he calls evolutionary design over visionary design. "Evolution is always away from known problems rather than toward imagined goals. It doesn’t seek to maximize theoretical fitness; it minimizes experienced unfitness," Brand writes. "Evolutionary forms such as vernacular building types always work better than visionary designs such as geodesic domes. They grow from experience rather than from somebody's forehead."

On one level, this line of thinking leaves itself open to charges of philistinism — charges that may not be entirely without merit. But it also expresses a highly appealing kind of methodical, incremental pragmatism, one I associate with an America yet to be infested with subdivision-developers and house-flippers. "When you proceed deliberately, mistakes don’t cascade, they instruct," Brand writes. "Low risk plus time equals high gain. This strategy treats the fundamentals of the living investment with attention and respect. The lesson of realty laced with reality is: 'Get rich slow.'" But the possibilities of evolutionary design are severely undercut by the ways in which buildings tend to be financed, as explained in some of Brand's extensive quotation of Christopher Alexander, for whom "a mortgage-bought building tends to be an over-packaged illusion of completeness that defeats any kind of incremental approach."

Better, Alexander says in the 1997 How Buildings Learn BBC television series, to use "the money you've got" to build a basic, functional structure with an intent to expand, refine, and revise it as additional resources come available over time. As much sense as this makes, it is, unfortunately, a way of building against which a variety of modern incentives and imperatives militate. "Every building leads three contradictory lives — as habitat, as property, and as component of the surrounding community," Brand writes. "Maximizing market value means becoming episodically more standard, stylish, and inspectable in order to meet the imagined desires of a potential buyer. Seeking to be anybody’s house it becomes nobody's." He actually praises the much-sneered-at Levittowns of America, which since their rapid postwar construction have become "interesting to look at; people have made additions to their houses and planted their grounds with variety and imagination."

The key factor here is time, a requirement of the evolutionary process that has produced many a beloved structure and the urban spaces they constitute. "The most admired of old buildings, such as the Gothic palazzos of Venice, are time-drenched," Brand writes. "The republic that lasted 800 years celebrated duration in its buildings by swirling together over time a kaleidoscope of periods and cultural styles all patched together in layers of mismatched fragments." The resulting impressions have inspired recent cargo-cult practices in the design of modern buildings and cities both: "American planners always take inspiration from Europe's great cities and such urban wonders as the Piazza San Marco in Venice, but they study the look, never the process." The ersatz urbanism of Los Angeles developer Rick Caruso comes to mind, though sheer lack of organic alternatives has ensured that his projects turn out to be fairly well-liked by the public.

Even leaving aside its town-square-shaped malls (which have, in any case, spread across the country), Los Angeles has long been reflexively criticized for having "no history." The charge is flimsier than it sounds: "Because it was first for so many years — it built the first freeway system, the first airport for jet airliners, the first mid-century modern baseball stadium, the first shoddy neoclassical cultural palaces — it is in many ways the oldest U.S. city," writes Los Angeles Plays Itself creator Thom Andersen in his liner notes to Jim Jarmusch's Night on Earth. Some of its distinctive mid-century constructions stand still today thanks to the agitation of historical preservationists. Acknowledging that their cause amounts to a "secular religion" (which manifests in their willingness to, for example, "lie down in front of bulldozers to save a 1930s Art Deco bus station"), Brand also offers them surprisingly unqualified praise.

This same section contains some of the most straightforward acknowledgments of preservationist motivations I've ever read. "Widespread revulsion with the buildings of the last few decades has been an engine of the preservation movement worldwide," Brand writes. "Shoddy, ephemeral, crass, over-specialized, the recent buildings display a global look especially unwelcome in tradition-enriched environs." Fair enough. The architecture critic Paul Goldberger (here described simply as a preservationist) points to "our fear of what will replace buildings that are not preserved; all too often we fight to save not because what we want to save is so good but because we know that what will replace it will be no better." Brand puts the question to the reader: "Wouldn’t you rather go to school in a former firehouse, have dinner in a converted brick kiln, do your office work in a restored mansion?" Well, I don't not want to do that.

It's passages like these, I suspect, that have drawn How Buildings Learn accusations of being an elaborate but deceptively unsystematic defense of Brand's personal aesthetic preferences. One can hardly see the book any other way when reading him enumerate the renovations of his writing office, "a derelict landlocked fishing boat named the Mary Heartline" (a reference I wonder if anyone under 70 gets today); his library, "a shipping container twenty yards away"; and the Mirene, a 1912 tugboat laboriously (but, in his telling, lovingly) converted into his and his wife's residence in the Sausalito harbor. More relevant to my own interests is his description of the neighborhood surrounding that last, a place "where zoning has broken down, partly because it's on the border between city and county jurisdictions," which opened it to invasion by "illegal residential houseboats such as mine, eventually over 400 of them."

"From my door it is a short walk not only to my office but to: public storage, auto repair, boat supplies, bike supplies, office supplies, film supplies, tire service, a car- battery manufacturer, a gas station, a gym, a notary public, a supermarket, a convenience store, a deli, and seven restaurants," he writes, describing an urban scene by no means metropolitan but still surely alien in its sheer convenience to many American readers of 1994. "I visit friends in nice homes elsewhere and it feels as if they live in a desert, zoned out of a walkable way of life, stuck in a place where nothing ever changes." Ideally, in his view, a city will change gradually over time — neither paralyzed by poverty nor overwritten by "quick-buck speculation and abstract investment" — retaining and repurposing traces of its every previous stage of evolution.

"The flow of money through and around a building acts to organize that building," Brand says in the How Buildings Learn series. "Will the building be organized around the moment of sale, or the decades of use? The same goes for cities. Will they be organized around quick-buck markets and brittle theories, or around the steady accumulation of wisdom, utility, and delight?" If Brand offers a prescription for cities in this book, it's that buildings should be more like them. "Following the outrages of 'urban renewal' in the 1950s, neighborhood groups organized, took power politically, and hired the planners to work for them," he writes in an appendix. "City planning used to imitate architecture, and it failed because of that. If architecture now began to imitate city planning, it could learn to succeed better"; we could one day have "buildings that flex and mature the way cities do."

This strikes me as a fine idea, as do many in the book, though what purchase it's found in the built environment over the past thirty years is harder to determine. I also like the notion of contributing to a city's evolution — to its accumulation of "wisdom, utility, and delight" — but the prospect of owning a building feels about as within reach as that of owning the International Space Station, to say nothing of the additional costs of renovation, adaptation, and maintenance (the subject of Brand's next book). Even converting a boat into an office seems too bewildering and costly to contemplate. Where do people get the money? Brand mentions having spent a few years running a consultancy called Global Business Network, an experience that sounds lucrative enough (and inspires a chapter on "scenario planning" in building design). He wasn't writing a Substack, I'll tell you that much.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His current projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.

the About Buildings and Cities chaps have covered this book too, with a more architect-y perspective. I am more in tune with the Colin Marshall critique personally, but it is always interesting to get some different views https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOHz8G6gPF8