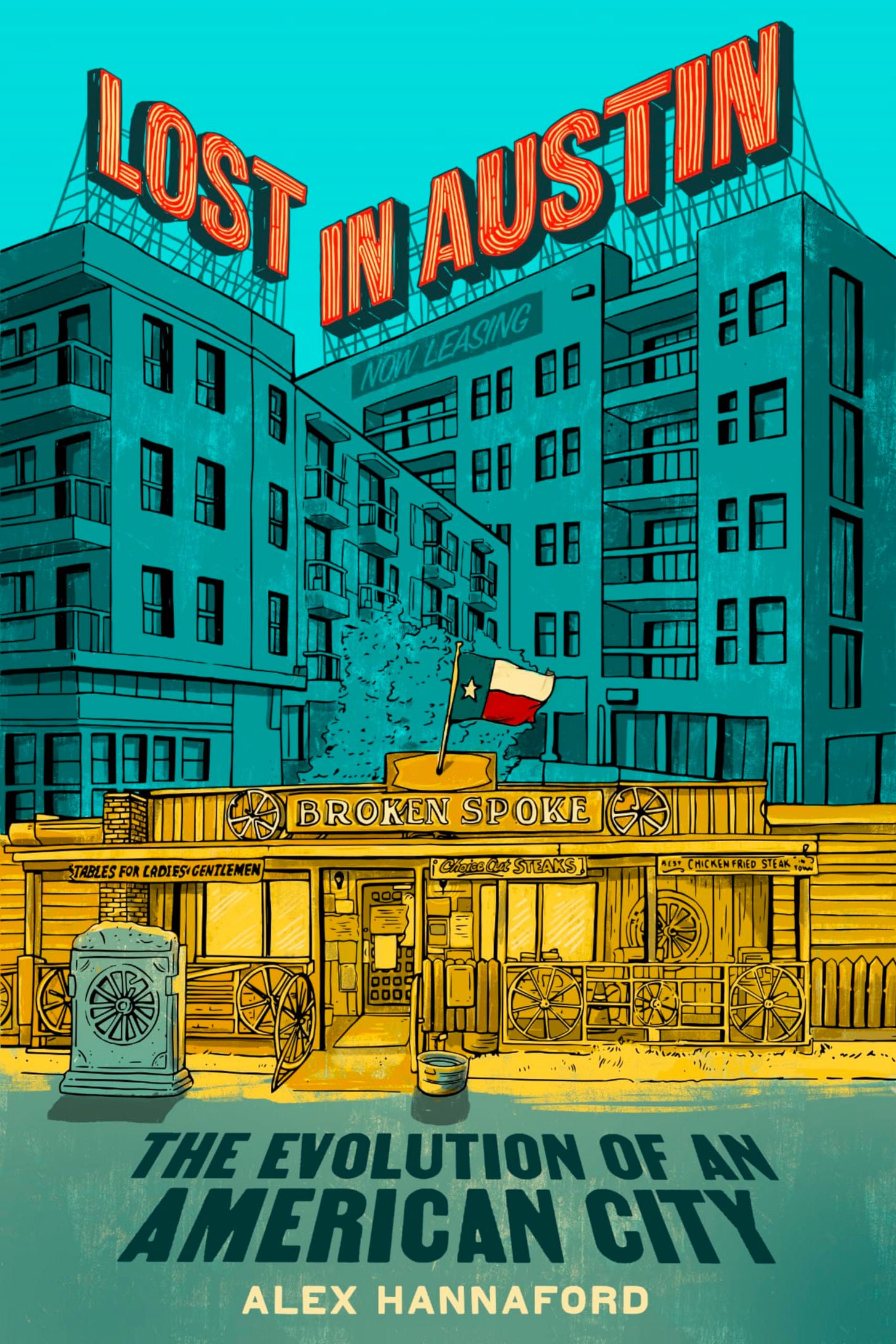

Alex Hannaford, Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City (2024)

How the Texas capital became too expensive, too ambitious, and too hot for its slackers

If you've never visited Austin, Texas, it's probably too late to do so now. That, in any case, is the impression I've received over the past fifteen years, during which time my interest in the city has greatly diminished. Word has long circulated that Austin is "over," but until now, there hasn't been a book declaring quite how over it is. Just this month, that book arrived: Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City, by a British reporter named Alex Hannaford. Enamored with the drifting, breakfast taco-fueled bohemianism of Texas capital since a road trip in 1999, Hannaford made regular visits thereafter, meeting the woman who would become his wife at South by Southwest in 2003. He put down down roots in what seemed like an ideal adopted hometown, and even started a family there. But within a couple of decades, he'd pulled those roots up.

What made Austin intolerable for Hannaford turns out to be the progression of trends that had long preceded his arrival. He'd much preferred the nearly year-round sunshine to the long stretches of unrelieved gray back in London, but eventually the climate became too hot to enjoy the local outdoor-activity culture as often as he once did. A spike in school shootings inspired fresh reservations about Texas' rate of gun ownership. The latest "tech boom," a successor of the one driven by the arrival of Dell Computer and the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation in the early eighties, brought Tesla, Apple, and Google to town, among many other smaller players, provoking real-estate bidding wars and waves of gentrification. And the increasing difficulty of keeping concert venues in business had made ever hollower Austin's brand of being "the Live Music Capital of the World®."

One might diagnose a larger failure to Keep Austin Weird, in the words of another, less formal slogan — and one the level-headed Hannaford also considers so much marketing. "It's true that a cross-dressing homeless man once ran for mayor three times," he writes. "And it’s true that every Sunday between 4:00 and 8:00 p.m. at the Little Longhorn Saloon you can still place your bets on which bingo numbers a chicken sitting on a platform above the table will shit on between the grilles (it’s called 'chicken shit bingo' for a reason). And we always saw some shirtless, thong-wearing guy cycling around downtown with a cat on his shoulder, but I don’t believe Austin has ever really been a weird city — just that it was, at least until recently, affordable enough for some really eccentric people to live there."

I have no more direct point of reference for Austin eccentricity than Slacker, the film whose success turned Richard Linklater into a major filmmaker. Shot in 1989, it "managed to perfectly capture Austin at a moment in time. It follows a ragtag bunch of misfits over the course of one day as they opt out of mainstream society. There are the philosophical grad students who pontificate over coffee and pastries, the hipster at tempting to sell what she insists is Madonna’s pap smear, and a conspiracy peddler who clutches a tall glass of iced coffee as he tags along with a student clearly uninterested in his ramblings." Hannaford doesn't say whether he feels any regret about not having experienced that particular moment himself, but every time I watch Slacker — which happens every decade or so, with greater appreciation of its rambling artistry each time — I certainly do.

For all my desire to step though the screen into it, the Austin of Slacker hardly looks like a city I, or anyone describable as an urbanist, would much enjoy. The streets Linklater shows exhibit a suburban density at the very highest, and the transit system seems to amount to a single taxicab in which an early scene plays out. But then, apart from a few rides given by one character to another, the chained-conversation structure of the film is built around movement on foot. Unmotivated though they may be, these slackers walk almost everywhere they go, mainly bookstores, coffee shops, and restaurants. Whenever I watch one evening scene, in which a few friends smoke and chat over a tableful of beer bottles and plates of half-eaten Tex-Mex, I feel as if I'm receiving a precious glimpse of a lost civilization.

Convinced to check out a show by young smooth-talker who claims to be on its guest list, these young women take the film into the realm of Austin's live music. A few character changes (and one Fisher-Price Pixelvision camcorder sequence) later, the scene is the Continental Club, still extant on South Congress Avenue. The act onstage has drawn only a handful of attendees, which, according to Linklater's commentary track, would register to a true eighties Austinite as not just a familiar vibe but also a deliberate joke: the band in question, a noise-rock outfit called Ed Hall, was enough of a local phenomenon to fill such a venue easily. They play a song "about Austin — like, having missed the boat. Whenever you're in any town, it's like this: 'Oh, you missed it. Before you got here, there was all this cool stuff going on, and now there's nothin' going on.'"

Linklater goes on to say that he "always resented that attitude, and never wanted to be like that myself. I think Austin's better now than it was. At this point in history, really, nothing was going on." Given that Linklater recorded the commentary track in 2004, Hannaford may actually agree with this specific claim, having settled in the city himself not long before. "There's a saying around here that the last day Austin was perfect was the day you moved to town," he writes. "It's certainly true today, but it's been true pretty much since the city was founded." This perception is also common in expatriate circles: it didn't surprise me to hear American here in Seoul who first came to Korea as a missionary say that, when he first arrived in the seventies, people were telling him he really ought to have come in the sixties.

Hannaford shows awareness of the most predictable potential criticism of his book: that he himself is just another transplant to Austin convinced that he caught the tail end of its last golden age. His rebuttal, simplified but not excessively so, is that it's different this time: "Perhaps the changes that Austin has undergone in the last two decades have been so profound, so expansive, that it's become a place only the rich can afford to move to; and perhaps that spark — that magic fairy dust that was sprinkled on the city by the very folks who can no longer afford to call it home — has gone forever." As he frames it, the city has about as much chance of getting less expensive, and thus less hostile to not-conventionally-ambitious eccentricity (if not out-and-out weirdness), as it does it does of getting less hot.

Another, slightly less obvious objection is that the process that has produced the Austin of today is also known as success. To take a more straightforwardly libertarian tack than I instinctively would: real-estate prices have increased because Austin has become more desirable, the architectural style (and scale) has changed in logical response to that demand, and the number of live music venues has decreased because Austinites no longer value them as much as other possible uses of urban space. On this subject, Hannaford quotes an unexpected source: a fellow Brit named Kevin Ashton, who's most widely known for having come up with the concept "Internet of Things" (and the even more dubious "smart city"). "Kevin reckons if we insist on having an unregulated market where everything goes to the highest bidder, we’re going to see a Starbucks on every corner, and that’ll happen, he says, 'because everybody buys fucking Starbucks.'"

"Saying 'I used to love Joe's coffee shop that my friend Joe ran but it's now a Starbucks' is privileged hand-wringing at its finest," Ashton says. A better way to mitigate the effects of gentrification, Hannaford writes, would be to figure out how not to have to "push certain people into longer and longer commutes, into neighborhoods that will be food deserts until they flip too and become gentrified." This could be accomplished by allowing for taller and denser construction, for which he doesn't seem to advocate, while also building a decent rapid-transit system, a goal of which he writes more approvingly, even as he takes a dim view of its prospects. The sole rail line in service (which is still one more than there was in the Slacker days) "doesn’t go to the university. It doesn’t go to the airport. It doesn’t serve south Austin. Or east Austin. Or west."

In 2020, Austin voters approved a fairly ambitious $7 billion expansion of the city's bus and rail network, which was scaled down severely within a couple of years due to the fast-increasing cost of acquiring the necessary land. In other words, "Austin’s growth and crazy real estate market meant that a plan to fix one of the very problems caused by that growth was being stymied by that growth, which had caused costs to escalate." This is the kind of passage Hannaford can point to if accused of opposing tech-driven growth per se, to which medium-sized cites have few apparent alternatives besides Rust Belt-style decay. What he opposes is growth at excessive speed: "A city can change and develop, but the consequences of rapid growth are dire. To grow so fast makes a city unaffordable, and the real thing you lose in a city growing too fast is its people."

Like most of the clichés I instinctively ridicule, that a city is ultimately its people has real truth to it. And it's no doubt also true that Austin, at least to the minds of some who preferred it in earlier times, has been invaded by the wrong people. Hannaford conveys more of Ashton's argument: "If enough people shop at the Walmart that apparently nobody wanted in the neighborhood in the first place, he says it’s going to stay there. What we’re really saying is we don’t want a place for those people to go." Though they probably aren't Walmart shoppers, Joe Rogan and Elon Musk have also relocated their operations from southern California to Austin; both are named in the book — and indeed, given a chapter title — as representative figures of the undesirable changes foisted on the city in recent years.

Rogan and Musk have also become bêtes noires of mainstream liberal American journalism, whose hectoring institutional voice occasionally manifests in Hannaford's prose. This doesn't bother me so much ideologically as aesthetically: the homogenization of American cities makes them not only "generic" and "soulless," but "less diverse and vibrant." The principles of Texan-style libertarian conservatism, underscored by the polar vortex of 2021, held that "government shouldn’t interfere. Freedom is paramount. You’re on your own. Except, of course, when it comes to women and what they wanted to do with their bodies." Climate change "and ensuing extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and wildfires, while affecting all of us, disproportionately impact marginalized communities." I'm reminded of how P. J. O'Rourke once summed up the perspective of NPR: "World to end — poor and minorities hardest hit."

I should reiterate here that Hannaford is British. After arriving in Austin to stay, he found that the kind of freak-show reportage "that illustrated how Americans and the British were two cultures separated by a common language seemed to land with editors back home: gun culture, executions, the border." But he sounds as if, like certain of his countrymen who emigrate to the U.S., he eventually went native and then some. His prose is riddled with Americanisms, including frequent references to "folks" and people or communities "of color," and even the occasional mention of a "bougie" grocery store or "impactful" satirical protest. But he also re-identifies himself with the the old country when criticizing Austin's apparent indifference to its built heritage: "We preserve old buildings not just as reminders of a city’s past but to help establish the character of a place — some permanence amid rapid cultural change."

Austin's newer buildings "look like they were built in a rush by contractors on a budget and architects without taste." So writes a relatively recent arrival in the city, a social-media personality called David Perell who styles himself as "The Writing Guy." (Theoretically, his advice should interest me, though from what I've seen, it tends to be of the "tell readers exactly why they should care within the first seven words" variety.) On South Congress Avenue, as he describes it, "you see the sterile, globalist, and hyper-contemporary aesthetic that defines so much of modern urban architecture. You have the same brands that you see in every major American city too: Equinox, Nike, Everlane, Alo, Lululemon, Allbirds, Sweetgreen, Warby Parker, and SOHO house — all of which are foreign to Austin’s native culture (seeing these brands in order is like a game of Millennial brand bingo)."

Though Hannaford would probably regard Perell as one of the tech-adjacent Johnnies-come-lately whose arrival signaled Austin's downfall, here the two agree. (Hannaford laments the transition of its urban persona from "a hippie in flip-flops chowing down on Tex-Mex watching a blues band in some dive bar to a guy in a pressed shirt, Patagonia vest, and Allbirds sneakers eating Japanese-barbecue fusion in an air-conditioned new-build.") Perell, however, comes off as unbothered by the presence of Tesla, Apple, and Google, and even a local "passionate cadre of Bitcoiners." He also looks askance at the inistence that the city on the whole has declined: "Though most of the longtime locals I meet say that Austin used to be better, they cite different years as Austin’s peak — usually the first five years they lived here. I’m not sure what to make of this, but it makes me skeptical of this-city-used-to-be-better claims."

Delivered, executive-summary-style, in the very first line, Perell's verdict on Austin is that it's "a mediocre city, but a great place to live." Apart from an observation about how it combines the ambitions of a larger city with the "long time horizons" of a smaller one, none of the qualities he mentions thereafter really intrigue me. There's certainly nothing to equal Hannaford's memories of his early Austin experiences with his wife: "Shannon and I would meet friends at Pace Bend Park out on the lake, where we’d take turns launching ourselves into the cool water from the cliffs, or laze around in floats, chatting and drinking beer. By early evening we were back downtown picking up cheap Tex-Mex to eat at my condo, barhopping on Sixth Street, or watching alt-country shows at the Continental Club. Days bled into one another. Mornings began with rocket fuel coffee from quirky cafés."

Hannaford gives a convincing impression that, fifteen-odd years after Linklater captured it, the Austin of Slacker still existed — and an equally convincing one that it has now vanished, never to return. Still, revisiting the film after reading Lost in Austin, it's hard to ignore its reflections of phenomena Hannaford cites as contributing to the city's degradation, from the peripatetic conspiracy-theorist's remarks on the worsening heat to the gun-toting young men (who, admittedly, have their own notable real-life precedent) to the Ron Paul campaign advertisement on the side of a truck. Even the heavy-metal dude toward the very end, rambling profanely and incoherently from a loudspeaker mounted on his slow-moving car, differs only in the technology he uses from the bien-pensant view of the average "Intellectual Dark Web" podcaster.

Linklater himself has admitted that the sample of Austin presented in Slacker isn't representative, either geographically or socially. I was reminded of this when I looked up the Google Street View of one of the intersections Hannaford mentions, that of Twelfth and Chicon Streets, near a soul-food joint he selects to represent the humble local institution in the crosshairs of gentrification. Having heard Austin described many times as a "city that feels like a small town" (which, in accordance with a common American prejudice, isn't meant as a criticism), I knew it wouldn't look like Manhattan. Still, I was unprepared to see a cleaner, more orderly version of the outskirts of a middle-tier Third World city — though that's slightly unfair to middle-tier Third World cities, which don't tend to give over large swathes of their blocks to surface parking lots.

I wonder if that comparison ever occurred to Hannaford, a former resident of both Lagos and Hong Kong whose whose worldliness extends far beyond the transatlantic. He does portray east Austin, in which Twelfth and Chicon is located, as a neglected "historically Black" (there, again, the NPR-ish phrasing) region of the city. But even so, I wondered, could this really be the same Austin everyone's been talking about? Late in the book, Hannaford quotes a local entrepreneur named Fred Schmidt as invoking "tons of really wonderful next-tier cities — new Austins waiting to be discovered," and some of them do a little better on the Street View test. Take, for instance, Sacramento, California, which, like Austin, is a state capital with a public university (albeit a much less well-regarded one), solid coffee shops, and for those who know where to look, high-quality tacos (if not usually of the breakfast variety).

Not that I imagine Sacramento developing the kind of culture that won over Hannaford on his road trip back in 1999. Even I next manage to take an American road trip of my own — about which I've come fantasize much more vividly since leaving the U.S. — I'll be tempted to stop in Austin in general, and Cisco's on Sixth Street in particular. "It's easy, when you're midway through your third cup of black coffee and your belly's full of migas, to look around this room of mismatched furniture and photographs of celebrities and politicians who regularly paid it a visit over the years and forget Austin's changed much at all," Hannaford writes of that beloved eatery. With no direct experience of how things used to be, I'd have no need to forget. I wouldn't fear Austin letting me down; I'd fear that I'd like it.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His current projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.