Edmund White, The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris (2001)

What the late examiner of American gay life learned from his expat years

Edmund White died this past summer at the age of 85, having lived about four decades longer than he must once have expected to. His HIV diagnosis came in 1985, around the height of the AIDS epidemic, when he was in his mid-forties. It can't have been a complete surprise, given that he'd spent most of the "golden age of promiscuity" that extended from the nineteen-seventies into the early eighties living it up in New York's "gay ghetto." There he was involved enough in the local scene to have been one of the original founders of Gay Men's Health Crisis in 1981, before the cause of the new plague had come to light. For a time, that group officially adopted the view that the underlying virus must require multiple sexual exposures to be transmitted, White remembers in his memoir Inside a Pearl, the assumption being that "promiscuity was to blame. Cold comfort for me, since I had had literally thousands of partners."

Whether that résumé point counted as a mark for or against him, White eventually ascended to the presidency of Gay Men's Health Crisis. "I hadn’t liked myself in the role of leader," he remembers, describing himself as "power mad and tyrannical." Wanting an excuse to abdicate that position seems to have been a reason for his relocation from New York to Paris in 1983, though not the only one: "Secretly I’d wanted the party to go on and thought that moving to Europe would give me a new lease on promiscuity. Paris was meant to be an AIDS holiday. After all, I was of the Stonewall generation, equating sexual freedom with freedom itself." Alas, that holiday soon came to an end, though the diagnosis didn't end up putting much of a cramp in his style. White himself proved genetically disinclined to sicken, let alone die, as a result of carrying HIV, unlike so many of the friends and lovers (not a hard distinction in his milieu, it turns out) he ultimately buried.

One of them, a young French architect-turned-illustrator called Hubert Sorin, ended his life as White's professional collaborator. The result was Our Paris: Sketches from Memory, a slim collection of illustrated vignettes featuring the eccentrics both obscure and world-famous with whom their shared life in the French capital put them into contact. With their alternating loose-rigid line and their lighthearted, faintly Art Deco-inflected aesthetic, Sorin's high-contrast drawings exude what I think of as the look and feel of the late nineteen-eighties. That charming book came out in 1995, the year after Sorin's death, as the first volume in White's already considerable bibliography to deal specifically with his time in France, spent mostly from the early eighties to the late nineties. Published in 2014, the much baggier and even more name-dropping (a tendency White openly admitted, and then heartily embraced) Inside a Pearl was the last. Between them, in 2001, came the less obviously personal The Flâneur: a Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris.

The Flâneur brought White to my attention, though I never did make it a priority to explore his work. His reputation had something to do with that: not his status as an avowed Gay Writer, but what I gathered to be his specialization in the detailed description of gay sex acts, a difficult proposition for even the most open-minded straight male reader. Indeed, his career is bookended by the co-authored The Joy of Gay Sex, from 1977, and The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir, published just this year, less than six months before his death. His 1982 breakout novel A Boy's Own Story, the first part of an autofictional trilogy, deals with the early homosexual experiences of a protagonist coming of age in the American midwest of the nineteen-fifties. A work of nonfiction not categorized among his memoirs, The Flâneur struck me as an ideal point of entry into White's oeuvre, one that could provide a sense of his prose and worldview without the risk of alienation inherent in a direct plunge into the sexual realm where he spent so much of his personal and professional life, so unabashedly.

Martin Amis, surely one of the straightest British novelists of his generation (and, incidentally, one of White's many famous Paris-frequenting friends described in Inside a Pearl), claimed that sex lies outside the reach of literature. "Sex is hard to write about because you lose the universal and succumb to the particular," he argued in one much-circulated quote. "We all have our different favorites." In some contexts, he also marshaled the words of (the French, gay) Henry de Montherlant, adding that sex, like happiness, "writes white." One could hardly put it past him to have spun that observation, at one time or another, into a pun involving the name of the writer under discussion here: sex writes white; White writes sex. The idea of approaching White through a book like The Flâneur wasn't about separating his work from his sexuality, which his books in any case show to be impossible. Gay life, and specifically the gay life of a cultivated American born during the Second World War, wasn't just a subject conveniently at hand, but one central to his literary project.

The word flâneur has gained a lot of popular traction — and to a tiresome degree, I would say — over the past couple of decades, but I do wonder how many English-language readers of any generation recognized it in 2001. White defines it early on as referring to the "aimless stroller who loses himself in the crowd, who has no destination and goes wherever caprice or curiosity directs his or her steps." The term's initial popularization by Baudelaire explains some of its association with Paris, as do the qualities of the place itself: its commercial robustness, yes, but also its continuity, its interconnectedness, and its consistently "beautiful" built environment. White calls the city "a world meant to be seen by the walker alone, for only the pace of strolling can take in all the rich (if muted) detail." Of course, it's no longer Baudelaire's "cozy, dirty, mysterious," Paris, which was "destroyed after 1853 by one of the most massive urban renewal plans known to history, and replaced by a city of broad, strictly linear streets, unbroken façades, roundabouts radiating avenues, uniform city lighting, uniform street furniture, a complex, modern sewer system and public transportation."

No one alive remembers Paris before its Haussmannization, but some remember Paris as it was before it became the world's most most tourist-visited city. That particular quality always gave me pause enough that I traveled to a variety of other world capitals before even considering setting foot there. It seemed to me that I'd need a strategy, not just to set myself apart from the tourists, but also to keep the ambience of tourism from impinging too severely on my experience of the city. The deliberate aimlessness of the flâneur was a promising option, not least because of its diametric opposition to the general way of the tourist. "Americans are particularly ill-suited to be flâneurs," White notes, and not just in their own cities, which tend to be unaccommodating or outright hostile to that practice. "They’re good at following books outlining architectural tours of Montparnasse or at visiting scenic spots outside Paris — the Désert de Retz, which is a weird collection of follies, for instance, or Rousseau’s gardens of Ermenonville, where he meditated in a temple built to resemble a Roman ruin. But they are always driven by the urge towards self-improvement."

The true flâneur isn't looking to improve himself on his urban walks — indeed, isn't looking for anything in particular at all. In White's view, "to be gay and cruise is perhaps an extension of the flâneur’s very essence, or at least its most successful application. With one crucial difference: the flâneur’s promenades are meant to be useless, deprived of any goal beyond the pleasure of merely circulating." During his Paris years, White himself seems often to have stepped out the door with one goal very much in mind. "In the beginning I’d cruise along the Seine near the Austerlitz train station under a building that was cantilevered out over the shore on pylons. Or I'd hop over the fence and cruise the pocket park at the end of the Île St Louis, where I lived." This was early in the gay-friendly François Mitterrand administration, which for a New Yorker felt like a blessed safe haven from police raids and "roving gangs of queer-bashers." All the Seine-proximate cruisers had to worry about was periodic illumination: "When the bâteaux mouches would swing round the island, their klieg lights were so stage-set bright that we’d all break apart and try to rearrange our clothing."

That's a memorable image, and about as explicit as White gets in The Flâneur. (Even Inside a Pearl, which parades a succession of lovers numerous enough to get mildly confusing, only goes as far as referencing such encounters as that with "a young Spaniard who’d worked my nipples so hard they were still aflame.") It's perhaps more vivid if you've ridden one of the bâteaux mouches, those long, low, open-topped ferries that make their looping runs along the Seine past the maximum number of historic structures. As it happens, my wife and I took a ride on one of them toward the end of our monthlong honeymoon in Paris a couple of years ago. The short cruise was more interesting than I'd have expected such a purely touristic experience to be, banal though a fellow like White would probably find its pleasures. In Inside a Pearl, he recalls walking his "sumptuous route home" and hearing them pass, making waves on the riverbank and delivering their "running commentary in English, French, Italian, and German." On our bateau-mouche, I noted at least three additional languages — Chinese, Japanese, and even Korean — which I suppose speaks to the ever-widening tourist appeal of Paris in the quarter-century or so since White was living there.

Tourism mostly comes up in the The Flâneur's opening chapter, which offers a potted history of the titular concept. Walter Benjamin devoted much thought to what makes a flâneur, not least through negative definition: "He (or she) is not a foreign tourist eagerly tracing down the Major Sights and ticking them off a list of standard wonders," in White's gloss. "He (or she) is a Parisian in search of a private moment, not a lesson, and whereas wonders can lead to edification, they are not likely to give the viewer gooseflesh. No, it is the private Proustian touchstone — the madeleine, the tilting paving stone — that the flâneur is tracking down." White wrote a biography of Proust, who comes up throughout this book, and of Genet, who does as well. Other illuminating figures brought to the fore by the flâneur's-walk-like structure include American entertainers like Sidney Bechet and Josephine Baker; the Camondos, a prominent nineteenth-century Jewish banking family whose only remaining trace seems to be one of Paris' many obscure museums; Gustave Moreau, whose paintings White describes as grimly kitschy yet strangely enduring; and the Spanish-born Louis XX, whom monarchy-minded Legitimists consider the rightful king of France.

Though brief, the book contains a good deal of history, which in any case constitutes much or most of the appeal of Paris itself for its serious, usually affluent appreciators. White only half-laments that the city has become a "cultural backwater," with a center "too expensive to welcome young bohemians or wannabe novelists, who've all fled to Prague or Budapest, even Riga." (The famed early-to-mid-twentieth century American expatriate writers like Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and James Baldwin came to Paris for a variety of reasons, the most compelling among them being its then-cheapness.) In Inside a Pearl he writes that the city is "full of things an older person likes — books, food, museums"; in Our Paris, that everyone there "seems to be the son or granddaughter or nephew of someone famous. The famous people themselves belong to the city’s glorious past; their relatives, like Parisians in general, are living off their patrimony." Yet "the French have such an attractive civilization, dedicated to calm pleasures and general tolerance, and their taste in every domain is so sharp, so sure, that the foreigner (especially someone from chaotic, confused America) is quickly seduced into believing that if he can only become a Parisian he will at last master the art of living."

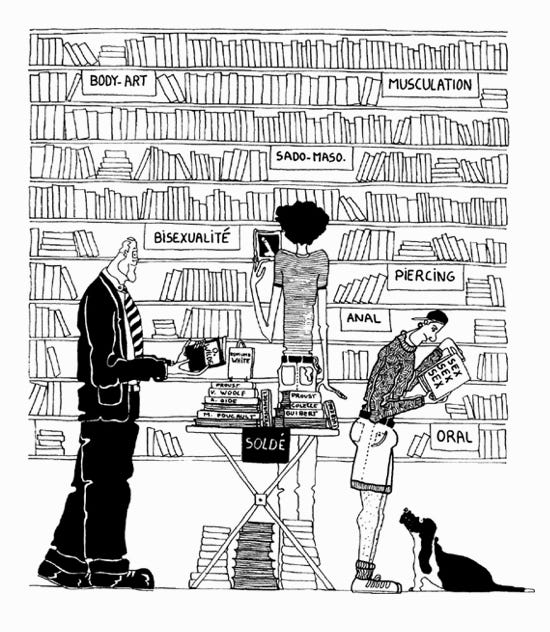

This "sneaking suspicion that maybe the French have got it right, that they have located the juste milieu," must have felt especially compelling within White's sub-milieu of ultra-cultured middle-aged gays. As would perhaps be expected, he inclines one of The Flâneur's chapters toward what we could call "gay Paris," as he deals in other parts of the book with "expat Paris," "black Paris" (or at least black American Paris), and "Jewish Paris." Yet to an extent, these are all contradictions in terms, as White acknowledges when he discusses a less-often acknowledged strengths of French civilization. "One of the great paradoxes is that France — the country that produced some of the most renowned pioneer homosexual writers of this century (Marcel Proust, André Gide, Jean Genet, Jean Cocteau and Marguerite Yourcenar, just to begin the list) — is also today the country that most vigorously rejects the very idea of gay literature," he writes. According to the official belief that "society is not a federation of special interest groups but rather an impartial state that treats each citizen — regardless of his or her gender, sexual orientation, religion or color — as an abstract, universal individual," recognizing "any subgroup of citizens is a diminishment of human equality."

France thus has writers who are black, none of whom are known as "black writers"; it has writers who are Jewish, none of whom write "Jewish novels"; and though "so many of the leading French writers of the twentieth century have written openly about their homosexuality," the "label 'gay fiction' evokes only a tired smile in Paris." This all sounds rather salutary to me, but then, it would: I'm from United States, a country driven halfway to the asylum by its own identity politics. I suspect it might also appeal to another of my countrymen who has lived in France and used it as a subject: David Sedaris, whose essays about taking language classes at the Alliance Française in Paris made me laugh harder than I'd ever laughed at anything to that point in life. (I immediately went to pre-order his forthcoming book, then tentatively titled Primates on the Seine.) Sedaris came to mind as I read Inside a Pearl, in which White references a remarkably similar Alliance Française experience of his own, right down to the strict, eccentric teacher and her jumble of cowed, unpromising students. Yet on the whole, the two men have far less in common than one might expect.

Sedaris may be a gay writer (and, come to think of it, he was probably the first one I read, or at least the first who was open about it), but he's not a Gay Writer. It wouldn't be too much to say that he's actively avoided that designation, having spoken in interviews about how he pulled his first book from imminent publication with a small gay press when he realized that route wouldn't take him to the general prominence in letters he'd envisioned. I remember reading it mentioned in another profile, long ago, that he has no interest at all in writing about sex, which has surely done its part to keep his work in the mainstream. So has the life he leads, based as it is on a decades-long monogamous relationship with a boyfriend who figures prominently in his writing. In the eighties, Sedaris once wrote, almost all the gay couples he knew "had some sort of an arrangement. Boyfriend A could sleep with someone else as long as he didn't bring him home — or as long as he did bring him home. And boyfriend B was free to do the same. It was a good setup for those who enjoyed variety and the thrill of the hunt, but to me it was just scary, and way too much work."

Edmund White, safe to say, lived for variety and the thrill of the hunt. Though always devoted, in some sense and in his own telling, to his various long-term lovers, neither he nor they seem ever to have even considered the possibility of conventional fidelity. Complexly quasi-familial domestic, financial, and travel arrangements resulted: taking both his current partner and a previous on a foreign vacation, say, while keeping also keeping the nights to himself for brief assignations amid shrubbery and under bridges. "I doubt that most women can understand how romantic anonymous sex can be," he writes in Inside a Pearl. "What men like about anonymity is that it allows free rein to any fantasy whatsoever. There are no specifics to contradict the most extravagant scenario." Though he liked to quote Camus' observation about American writers being the only ones in the world who aren't intellectuals, White did have his intellectual tendencies of his own. As such, he must also have enjoyed what I once heard Andrew Sullivan, in an interview with Tyler Cowen, frame as "the good thing about being gay": that it brings you into frequent contact with individuals of a "totally different socioeconomic group than you are through sexual and romantic attraction."

In this sense, the straight flâneur is at a disadvantage when it comes to understanding a city at all its levels. He may dream of a walk suddenly putting him face to face with the woman of his life — always, though he may not realize it, of roughly equivalent background to his own — or he may exorcise his desires in a more utilitarian fashion, with the aid of professionals. (The latter strategy, I suspect, has been fading into a thing of the past for quite some time now. In Paris, the prostitutes who stood daily in the same spots on the sidewalks and in the doorways of our neighborhood held no allure apart from that of the quaint anachronism.) No matter what, there remain swathes of society with which he never enters into intimacy of any kind. Not so the gay intellectual, a thoroughly urban figure from whose distinct vantage White looked throughout nearly 50 years of steadily published fiction, memoirs, and essays. White's life placed him well to understand this, including though it did stints in relatively bucolic regions of America and France. He was, after all, what (in a style that had become "simpler and more direct because of living in two languages") he titled his memoir on New York in the sixties and seventies: a city boy.

See also:

Lawrence Osborne, Paris Dreambook: An Unconventional Guide to the Splendor and Squalor of the City (1990)

Harold Brodkey, My Venice (1998)

Donald Richie, Tokyo: A View of the City (1999)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His latest book, published in Korean, is 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea). Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.