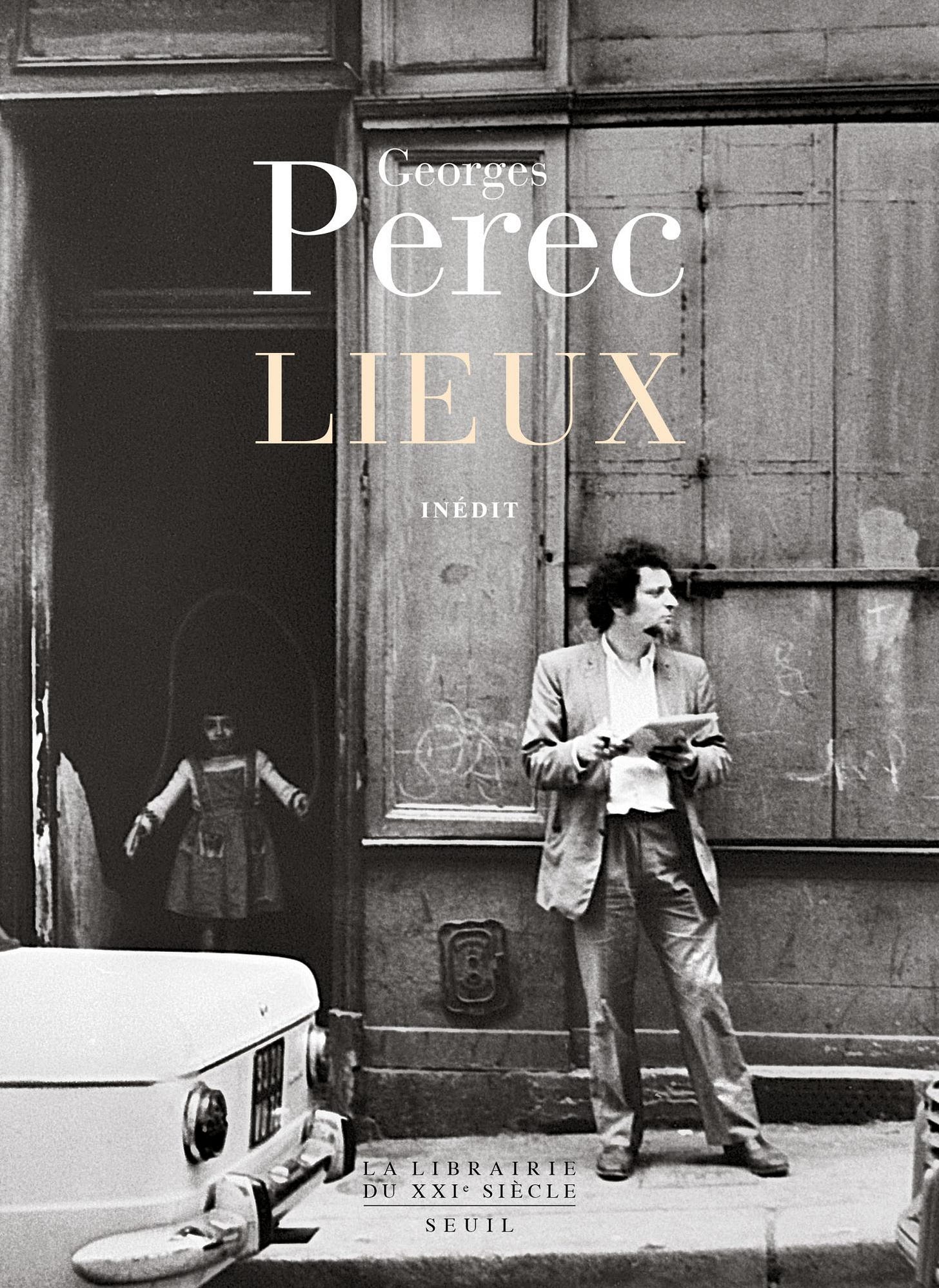

Georges Perec, Lieux (2022)

In 1969, Georges Perec launched himself into a twelve-year-long project to describe twelve meaningful places in Paris — a project that went unseen by the public until four decades after his death

Georges Perec was born in Paris and died in Paris (or at least a suburb just across the Périph), which didn't necessarily qualify him to write about the city. Natives of a place tend to suffer from a degree of what-do-they-know-of-England ignorance of context, or even, to get more metaphorical and more clichéd, the fish's unconsciousness of water. Why Perec could pull it off surely owes in part to his stints living elsewhere — boarding school in the Alps, a newlywed year in Tunisia — and in larger part to his sheer unconventionality as a writer. This is a man who wrote one novel structured by an all-knight's-move journey through an apartment block, and another that, in 300 pages, never once uses the letter e: just two of the best-known achievements in a body of work mostly composed under similarly strict rules, methods, and constraints.

A member of Oulipo, the Ouvroir de littérature potentielle whose members dedicate themselves to the use of just such rules, methods, and constraints, Perec is remembered today as an experimental writer, albeit one whose work is credited with an accessibility, humor, and even feeling not usually associated with that label. These products could emerge from improbable processes: take the minor entry in his canon Tentative d'épuisement d'un lieu parisien (An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris), a 60-page book consisting of neutral-sounding observations made during three days in 1974 spent sitting at Place Saint-Sulpice: “I am sitting in the Café de la Mairie, a little toward the back in relation to the terrace.” “A woman goes by; she is eating a slice of tart.” “Two free taxis at the taxi stand.” “Three children taken to school. Another apple-green 2CV.” “A bus. Japanese.”

Today, a trompe l'oeil plaque at the Café de la Mairie declares its terrace “Place Georges Perec” — or, rather, “PLAC G ORGE S P R C.” I went to see it a few months ago on a language-practice-trip-turned-honeymoon (long story) in Paris, inspired by a talk from Perec's Korean translator here in Seoul. For reasons literary or otherwise, the Café de la Mairie is a popular spot. My wife and I had to hang around for quite some time before a table opened up, and even then we never did seize the moment to flag down one of the pair of harried waiters on duty and order. It was just as well, since nothing on the menu seemed especially appetizing, and the ambience wasn't right: it was still mid-evening, when the true Parisians around us were still just drinking and smoking, whereas we had a Bateau Mouche to catch.

Not everything we did in Paris was so classically touristic. We spent a month there, a period of time too long — by design — to fill entirely with landmarks. Many days found us visiting bookstores, our standard traveling procedure in any part of the world. This resulted in our luggage being filled to the absolute limit on the flight back, though among all the books we bought, there was only one I'd been determined to find beforehand: Perec's Lieux, published by Editions Seuil just last year, four decades after the author's death. A volume weighty enough to preclude the purchase of many a souvenir, it collects all of the material Perec generated while working on an ambitious and characteristically programmatic writing project from the late nineteen-sixties to the mid-seventies, one organized around a highly specific set of lieux in Paris.

As Perec described it in a letter, the idea — “assez monstreuse, mais, je pense, assez exaltante” — was to choose twelve places in the city, all connected in some way with his own life. Starting in 1969, he would describe two of them per month, one by going there physically and recording the sights as objectively as possible (as he would do with Place Saint-Sulpice for that unrelated book), and another by going there mentally, recalling all his memories associated with it. This he would accomplish over the course of twelve years, following a table algorithmically devised through correspondence with Indra Chakravarti, a statistician at the University of North Carolina. (One element to recommend the print edition of Lieux over the e-book is its inclusion of the resulting bi-carré latin d'ordre 12 as a separate artifact, reproduced at a size about a third larger than a postcard.)

Each month's texts went into one of a series of envelopes, all of them to be sealed, in theory, until the project's completion at the end of 1980. In practice, it didn't happen that way: production of the film adaptation of his novel Un homme qui dort overtook nearly the whole of 1973, and though Perec did manage to resume the project the following year, the last document in its last envelope is dated September 1975. He published elsewhere some of what he'd written about these places, souvenir and réel, in the remaining years of his life, but most of the envelopes weren't opened until a few years after his death. Their complete contents never appeared in book form before Lieux, whose 600 pages include reproductions of certain of Perec's handwritten pages, as well as of diagrams, receipts, telegrams, invitations, and photo contact sheets shoved in there with them.

They also include a section of endnotes voluminous enough to delight the detail-oriented Perecophile (if that isn't a redundancy). I read the book start-to-finish, following the chronological order in which it presents the texts, and — employing the bi-carré latin as a rear bookmark — flipped to the back for each and every note. In many cases, the information provided is trivial: an alteration between manuscript and typescript, a clarification that the “rue du Général-Leclerc” is in actuality an avenue. But the organizers of Lieux, edited by Association Georges Perec president Jean-Luc Joly, have also identified every person, business, and cultural work Perec mentions, or at least attempted to. Possessed of a busier social life that I'd imagined, he refers to many of his acquaintances by initials or given name alone, and in any case takes no great care with the consistency of their spelling.

“Perec était cinéphile,” one note explains, “apprécait particulièrement le western et” — a real Frenchman — “vouait presque un culte à Jerry Lewis.” A street scene on Île Saint-Louis involving une vieille épouse de tycoon and une gigantesque Lincoln puts him in the mind (“je ne sais pourqoui”) of Sunset Boulevard. Rue de la Gaité in Montparnasse gets him reminiscing about the grands axes cinématographiques of Paris on which he did his formative moviegoing. Visiting that street the following year, he notices an ongoing “James Bond festival” — whose name, an endnote adds, was “Viva James Bond.” That there seems always to have been some Bond movie or other playing in those years is just one of the cultural background details that Perec might have called infra-ordinaire, and whose presence in the text fascinates me. (Another is that the same period was evidently a big one for Georges Moustaki).

Lieux is the rare book composed, in a sense, almost entirely of background details, not that Perec could have foreseen its nature at the time. Some of his own remarks indicate that he wasn't sure what form, if any, the result of his tour des lieux would ultimately take, though he does articulate — and critique — his reasons for doing it. The whole thing started, it seems, with a breakup: his paramour had been a wealthy older woman named Suzanne Lipinska, who presided over a kind of artists' colony near Rouen called Le Moulin d'Andé. (His marriage, I gather, had long since begun its prolonged French-style dissolution.) In near-suicidal despair, Perec chose these twelve places not just in search of something to do, but also “to root myself in Paris”: an “obviously hypocritical” rooting, since it technically required him to be in the capital only once per month.

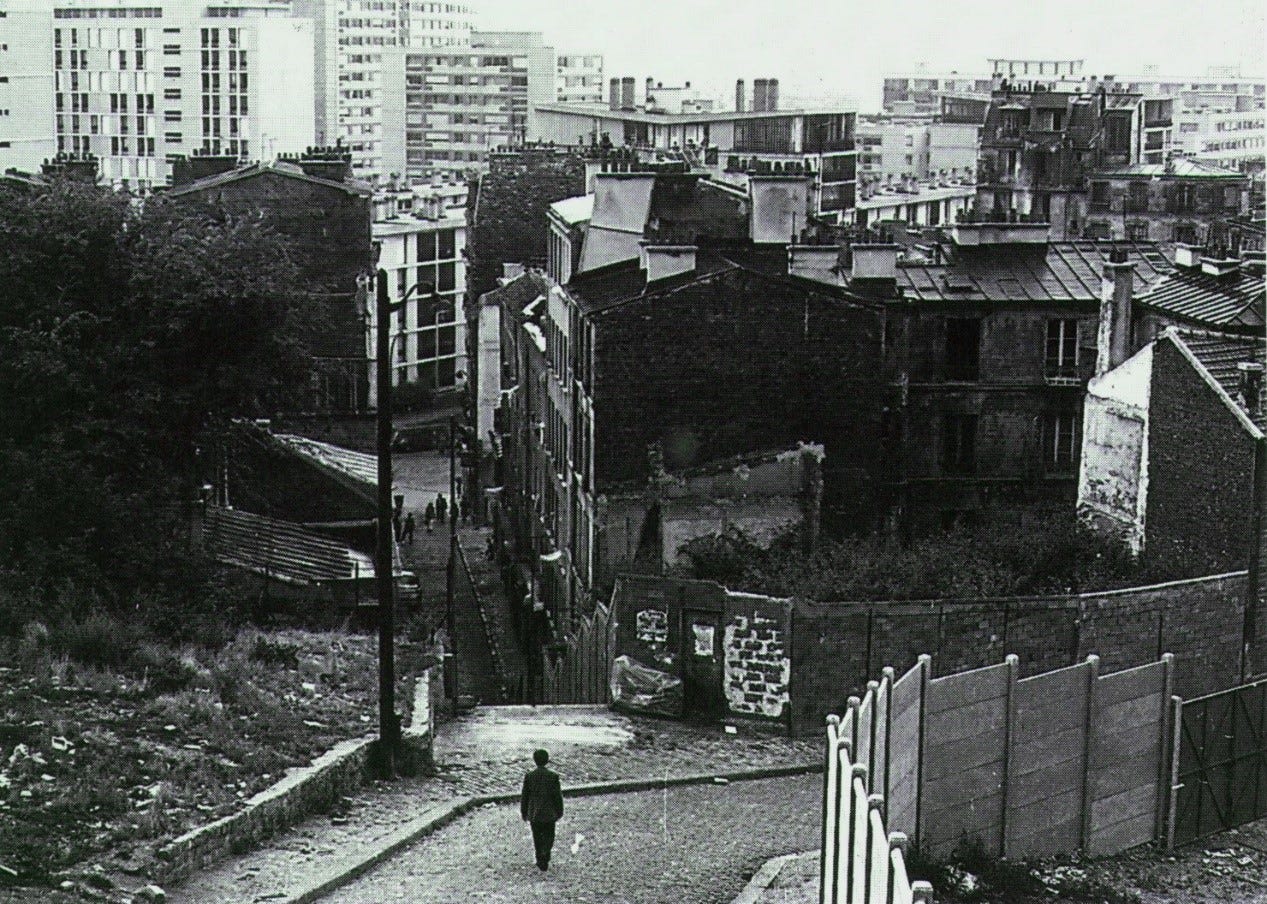

The aforementioned Île Saint-Louis — the other island in the Seine, next to the one with Notre-Dame — made Perec's list because Lipinska had an apartment there (which, today, would surely get him branded “creepy”). Other places, like Passage Choiseul and rue Mabillon in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, were connected to his not-quite-ex-wife Paulette. Rue de la Gaité, avenue Junot, and place d’Italie had been home to friends or family members. Half of his selections are areas where he himself had lived, from place de la Contrescarpe and place Jussieu to avenue Saint-Honoré, the address of his student room, and Belleville's rue Vilin, the Jewish neighborhood of his childhood whose later redevelopment stirred in him complex, work-inspiring feelings (entangled, naturally, with the deaths of his parents in the Second World War). Unless you know Paris well, you probably haven't heard of most of these places; I know I hadn't before going there.

Perec was in his late thirties when he abandoned the project that would become Lieux. I was in my late thirties by the time I first set foot in Paris. Was it supposed to take that long? Having been born and raised on the west coast of the United States when I was primed me, you could say, to develop not a Europe- but an Asia-facing cultural awareness. In high school, I tuned out classmates who returned from European summer vacations to deliver ostentatious paeans to quaint cafés and lively boulevards; in college, I disdained the standard American post-graduation rite of Eurailing through a dozen countries in as many days. (I was not, of course, in a position to do either one myself.) Yet as my intellectual focus turned thereafter toward cities, I realized that there must be unignorable and nowhere-replicated urban value in the capitals of Europe, especially Paris.

Even so, I had no desire to be a tourist anywhere, much less in a city filled with other tourists. Though it feels more or less constant across much of the Paris of the twenty-twenties, at least in my experience, their presence seldom comes through in Perec's observations of the sixties and seventies. “A few tourists,” he writes one afternoon in 1975 on avenue Saint-Honoré, making a rare foray into English, though the most part he identifies them only by their buses, and then only a few times over the course of more than five years. If you want to avoid the tourists of Paris — at least, the non-Perec pilgrims — you could do worse than to spend your time in the lieux of Lieux, a tool to plan your own walks through which is available on the book's official web site.

In that case, you'd do well to subtract the roundabout at Franklin D. Roosevelt station, near which Perec lived during an pubescent “fugue” of the late nineteen-forties. It happens to lie on Les Champs-Élysées, “un endroit que je n'aime pas.” In childhood Perec long believed, as he writes in a later souvenir passage, that it was really the center of Paris, a misconception he blames on its price in the French version of Monopoly. To me it feels more like an open-air international airport-terminal shopping mall, and during our month in Paris, Franklin D. Roosevelt station became the default portal back to the more interesting part of town where we were staying. I imagine Champs-Élysées as the point of overlap between Perec's Lieux and an inverted touristic version of his scheme, which would demand monthly excursions to places like Notre-Dame, the Louvre, Shakespeare and Company, and the Eiffel Tower.

Punishing though that sounds, would it not be a salutary exercise for the jaded Parisian? My online French teacher did something similar not long ago, and when we met up during my stay in Paris, he betrayed a certain enthusiasm in showing me the pictures he'd just taken in places like Montmartre and the Luxembourg Gardens. The vital factor, perhaps, is that, though born and raised in Paris, he's lived in Tokyo for years now; his latest trip to his hometown just happened to overlap with mine. I was recently brought to think about this again by Walker Percy's “The Loss of the Creature,” an essay about how excessive deference to expert opinion and familiarity with the “symbolic complex” of a place makes the tourist unable to experience the place directly — and how that direct experience “may be recovered by leaving the beaten track,” as at the Grand Canyon.

It may also be recovered “by a dialectical movement which brings one back to the beaten track but at a level above it. For example, after a lifetime of avoiding the beaten track and guided tours, a man may deliberately seek out the most beaten track of all, the most commonplace tour imaginable: he may visit the canyon by a Greyhound tour in the company of a party from Terre Haute — just as a man who has lived in New York all his life may visit the Statue of Liberty.” Percy adds that “such dialectical savorings of the familiar as the familiar are, of course, a favorite stratagem of The New Yorker magazine,” though that wasn't quite the tack I took when writing my own New Yorker piece in Paris. It was, however, about a tourist attraction, of sorts: the Tour Montparnasse, the central city's much-resented only skyscraper.

I wrote about the Tour Montparnasse not just because it's the kind of blandly extravagant nineteen-seventies commercial building that, for whatever reason, fascinates me (see also John Portman's Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles), but also because it happened to turn 50 years old while I was in Paris. After a prolonged process of negotiation and preparation (including the demolition of the neighborhood on its intended site, which like the young Perec's rue Vilin had been declared an îlot insalubre), it began construction in 1969 and opened in 1973, which means Perec would have witnessed it rise at least month by month on his Lieux visits to rue de la Gaité. “Paris se hérisse de buildings,” he declares in 1972, noting the “hauteur insoupçonnée de la tour Maine-Montparnasse,” using its original name from the context of its surrounding development project.

The Tour Montparnasse is only the most dramatic of the additions to the urban environment registered by Perec. Others include parking meters (Perec called these novelties parks mètres, according to an endnote, though the word is parcmètres), an escalier mécanique at Jussieu station, and, toward the mid-seventies, a sudden preponderance of Japanese restaurants, some of which have replaced establishments he used to know. While reading the book, I looked up some of the bars, cafés, and restaurants he mentions. More than a few turned out to be in business still today, half a century later, which definitely wouldn't be the case in, say, Los Angeles. These include Saint-Germain's La Rhumerie Martiniquaise (now just called La Rhumerie), where he recalls having committed a semi-accidental drink-and-dash with Paulette on the very first day of their relationship, each of them willfully but wrongly assuming the other had paid the bill.

This aligns with my impression that, by comparison to other world cities, Paris doesn't change much (the most visible legacy of Tour Montparnasse, for instance, is ban on tall buildings), which has perhaps instilled in Parisians a degree of inability to deal with change itself. I've never forgotten this Hacker News comment on Paul Graham's essay “Cities and Ambition”: “Being able to choose a place to live strikes me as so American; reading the article I realized I've never considered the possibility of living anywhere else than where I was born (Paris).” Underscoring the point, the commenter adds that “I feel a little bit like a tree: if I move I'll probably die,” which brings me back to Perec's stated aim of rooting himself in Paris (“m'enraciner à Paris”), though it must be said that he comes across as pretty well rooted in the first place.

Reviewing David Bellos' biography of Perec in the New York Review of Books, Geoffrey O'Brien Perec's lifestyle in what sounds like the Lieux era as follows:

He lives in one of the great cities, migrating every few years from one inexpensive apartment to another. His friends think he’s an absolute genius but the critics shrug their shoulders. He’s written masses of unpublished novels, poems, plays—and the books that he did publish failed to earn him much of a reputation; he showed great promise with his early work, but that was years ago. He hangs around on the fringes of the city’s intellectual circles, never in the limelight; he gets involved with political splinter groups without any real influence. He likes to drink; he smokes far too much; he’s in therapy. He goes to the movies a lot. He plays cards. He plays pinball games. He supports himself, year after year, as a glorified filing clerk in some sort of scientific research laboratory.

Between these activities he walks the city, with or without a destination, according to Oulipo-like prescriptions or not, observing the surface life of the city along the way. Here I would normally try to avoid the word flâneur, but Perec himself employs it in a variety of forms: flâner, flânent, flânant. He explains his choice of Passage Choiseul, which he'd only ever passed through, as a symbol of the Parisian arcade (in the Benjamnian sense) itself, “à la limite, le signe de la promenade, de la flânerie dans Paris.” He has more personal experience with another, whose name escapes him but which he describes as running from rue Drouout to Grands Boulevards. The relevant endnote acknowledges that “la topographie perecquienne des passages parisiens est assez confuse” before determining that this must be Passage des Panoramas, a block down the street from the bookstore where I bought my copy of Lieux.

“Je n’ai pas de souvenir du passage Choiseul,” he admits in 1974, clearly running out of steam. The entries get shorter and shorter, when he manages to write them at all; the final one begins with the equation “travail = torture.” After spending enough time with this long and discontinuous but strangely readable book, I found myself comparing not so much my and Perec's experiences of Paris as our experiences of launching ourselves into demanding long-term enterprises that crap out. Distractions are always a factor, though in Perec's case, some of those distractions turned out to be his most acclaimed works, including the film of Un homme qui dort and books like W ou le souvenir d'enfance (W, or the Memory of Childhood) and La Vie mode d'emploi (Life: A User's Manual), each of them inspired or shaped to one degree or another by the work that went into Lieux.

In the final analysis, this project could simply have been what Perec needed to do at the time to move forward personally and professionally. Reading Lieux today, one could hardly resist considering the potential benefit to oneself of schematically visiting (and/or envisioning) a dozen places relevant one's own memories, writing about them over and over for the next dozen years. Alas, for us children of American suburbia, that would be impractical to the point of absurdity: with even the most important places in our early lives tending to be isolated and distant from us or each other — not places at all, in the sense under discussion here — we can hardly relive various chapters of our lives with Proustian vividness by walking down an avenue. For us, this may be a central question of Perec's life and work: when you start in Paris, where can you go from there?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His current projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.