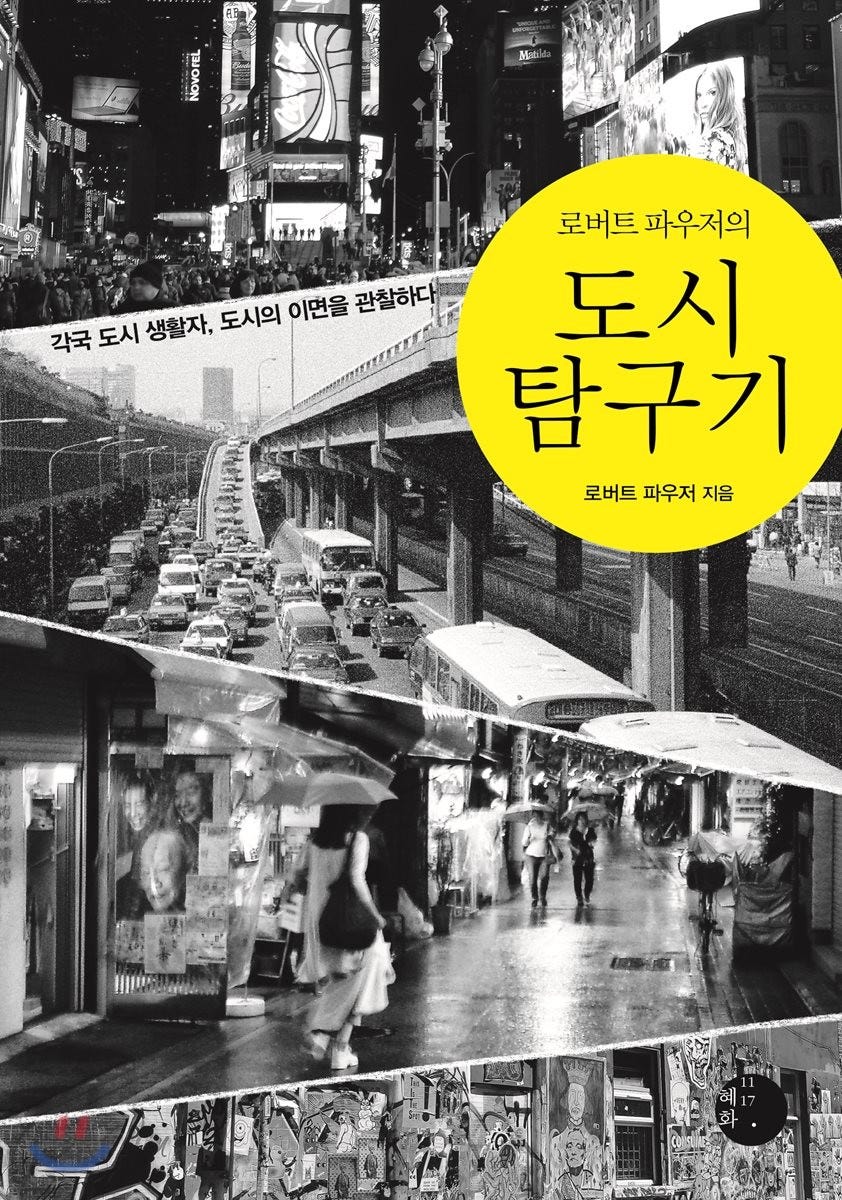

Robert Fouser, Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser (로버트 파우저의 도시 탐구기) (2019)

An American linguist-urbanist remembers the cities he's known, from Ann Arbor to Tokyo to Dublin to Seoul — and does so entirely in Korean

Robert Fouser left Korea in 2014, the year before I arrived. By that time he'd spent a total of thirteen years living here, most of them working as a professor at Seoul National University. Over the previous few decades, he'd also lived for considerable stretches of time in Japan, where his work included teaching the Korean language — and doing so, I should note, as an American. This strikes Westerners as a stranger arrangement than it did his students themselves, for whom, in his telling, it seemed no more remarkable than being taught Korean by a Korean; a foreigner is a foreigner, after all, especially in Japan. Still, any American without east Asian heritage who manages to teach Korean in Japanese commands my respect, given my own years of sure-to-be-lifelong struggle with both languages.

Putting teaching behind him and returning to the United States seems to have shifted Fouser's writing career into a higher gear, especially — and ironically — his writing in Korean. Over the past six years, he's published five books in this country: A Manual of Democracy for Koreans (미래 시민의 조건), Seochon-holic (서촌 홀릭), Spread of Foreign Languages (외국어 전파담), Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser (로버트 파우저의 도시 탐구기), and Learning Foreign Languages (외국어 학습담). These titles suggest an uncanny overlap between his interests and my own. I have noticed, at least in my own circles, a tendency of Westerners invested in the Japanese and Korean languages also to be invested in architecture and urbanism. But as far as I know, no others have written entire books about languages and cities in Korean.

Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser comprises chapter-length essays on Ann Arbor, Tokyo, Seoul, Daejeon, Dublin, Kumamoto and Kagoshima, Kyoto, Las Vegas, Jeonju and Daegu, New York, and Providence. Fouser has resided in most of these cities and been a frequent visitor to the rest: his relationship with New York, for instance, began while growing up in Michigan and looking to it as the metropole; much later he got to know Las Vegas by visiting his mother, who'd retired there. One could call the book an "urban autobiography," a form of writing all but the most thoroughly rural or sedentary among us could theoretically practice. I've been exploring cities for about twenty years less than Fouser has, but I could still put together an urban autobiography involving San Francisco, Seattle, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and Seoul (perhaps with the likes of Toronto, Osaka, or maybe even Sacramento thrown in there).

However low its barrier to entry, writing an urban autobiography at a high level does demand the skills of a city critic. I first sketched out that concept in a Guardian piece a few years ago, though I daresay it has yet to catch on. One could argue that cities, unlike more fixed and clearly definable works like books and films, don't admit of criticism per se. But I can't shake the feeling that what I'm reading in a book like Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser are, in effect, city reviews. Not they that bear any of the most obvious marks of that form, such as ratings out of five stars or recommendations of cities worth the reader's time and money. But even in the arts, such tropes belong mostly to the hackiest critics, those who conceive of their work as a kind of glorified consumer reporting.

Unlike the hacks, Fouser understands not just the nature of his subjects, but also the value of approaching them through his own life and experience. I could write an entire essay rattling off my dissatisfactions with the work of most film critics active today, but in order to draw parallels with city criticism two broad and recurring complaints will suffice. First, they seem not to have seen enough movies (or not reflected sufficiently upon the movies they have seen) properly to contextualize the one they're writing about; second, they seem not to have seen the one they're writing about enough times to go far beyond their own first impressions. They labor, one could say, under an underdeveloped relationship to cinema, or at least under an unwillingness to make full use of what relationship to cinema they do have, with the result that they consider each film in near-isolation.

Fouser's perspective is enriched by his not just having been to all the cities in this book more than once, but also by having revisited them over long periods of time. His most recent sojourn in the United States has been punctuated, apart from the pandemic years, by regular trips back to Korea and Japan. Relevant to this way of life is an observation made to me by Lawrence Osborne, which I quoted when writing about his Paris Dreambook: "Our relationship to cities is very much like our relationships to a person," he said. "What you really do is drop in over and over again, you get to know that person over a very, very long period of time. And when that happens — ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five years — the accumulation of those visits, the accumulation of that time spent, produces in you complex feelings."

Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser turns out to be a book of more complex feelings than at first it seems. Much as dropping in on people over the decades enables one to more sharply register the changes in them — as well as in oneself — dropping in on cities over the decades throws into relief the ways in which their built and social environments no longer conform to one's memories. But the changes in many of these cities, as Fouser sees it, haven't added up to absolute improvement. He first experienced Tokyo in the late nineteen-seventies, as a student on a two-month home stay, and the book contains the photos he took while walking its streets. Though he arrives in Tokyo with a spring in his step still today, he also acknowledges a dimming of the city-of-the-future glow it exuded during Japan's economic boom 45 years ago.

Little remains of the convivial Dublin Fouser knew while doing his Ph.D. in applied linguistics at Trinity College; a return visit presents him with neighborhoods that have grown rich but been sapped of all liveliness. As for New York, when he wants to get a bagel there these days, he ends up with the same texture- and flavorless rendition sold at Starbucks locations the world over. I don't think it would be too much to say that, in most of the cities he addresses in this book, Fouser senses a certain loss of vital essence that had been in greater abundance when he first came to know them. It is his hometown of Ann Arbor, to which he moved back upon leaving Korea, that inspires him to explain to his Korean readers a thoroughly American saying: "You can't go home again."

Elsewhere, Fouser also explains the thoroughly Portuguese concept of saudade, a kind of melancholic, alienated nostalgia. In Seoul, he invokes it to describe what he feels in the absence of those he knew there in decades past; in Kyoto, to describe what he feels when reminded of the time spent there with his mother on her visits when he resided in Japan. For an American like me to read a countryman use a Portuguese word in Korean to convey the experience of a Japanese place induces a kind of cultural vertigo. (Or I wish I did; admittedly, I seek out this kind of thing actively enough to have become long since used to it.) But to Koreans, who've heard their whole lives about their own supposedly distinctive and untranslatable emotions like han, jeong, and heung, culturally specific feelings will hardly be, as it were, a foreign notion.

Saudade is one thing, but ordinary nostalgia presents a major pitfall in this kind of writing. (There are writers I consider at least city criticism-adjacent who've more or less made their homes in that particular pit.) A longing for a city as it was in the past causes blindness to the city that exists in the present, though some sufferers do display a self-awareness about it: Donald Richie ends his book on Tokyo with the line, "Fifty years from now, this time about which I am complaining will probably have become someone else’s golden age." And yet, to my mind, Fouser does seem to have caught some kind of golden age in at least a city or two; I've wondered more than once whether I'd give up everything I have for just a year in the bubble-era Tokyo shown in his own photographs included in the book.

In recent years, nostalgia for Japan in the nineteen-eighties has inspired minor pop-cultural movements, especially among those who didn't experience Japan in the nineteen-eighties. This has also, at some delay, happened in Korea, which has lately enjoyed its own recent-historical television dramas and "newtro" design trends. Though writing on Korea in English has never been published in great abundance, the run-up to the 1988 Olympics, South Korea's debut on the developed-world stage, brought about a small burst of books by Westerners. (None are widely remembered today, but Michael Stephens' Lost in Seoul remains a favorite of mine.) The society they depict tends to come off as a harsh, often strange, and — with its curfews, air-raid drills, tear gas-clouded student protests — essentially martial. Still, the writers all end up with a fondness or at least admiration for Korea, if not feelings strong enough to make them live here.

Fouser's experiences of Korea in that era, first on visits from Japan and later — like so many Westerners after him — to teach English, seem to have proven more compelling. Part of that must have had to do with his actually learning the Korean language, still an uncommon achievement among even among Korea's long-term expatriates. This country's outward obsession with English belies its seemingly permanent inaccessibility to non-Korean speakers, many of whom take their own inability to communicate for an essential dullness or superficiality in the country itself. And though Korea's "English cancer," as I call it, must have set in by the eighties, a foreigner first arriving in that decade would have felt a more pressing need to use Korean in everyday life. (In a pinch, as the Japanese-speaking Fouser discovered, one could reliably communicate with the older generations in the language of the former colonial power.)

Whatever its drab developing-world rigors, pre-Olympics Seoul clearly had charms of its own as well. Almost none of its faces bore the marks of cosmetic surgery, as seen in the street photographs of that era by Fouser and others. As for its built environment, much less of the city had been demolished to build complexes of ten, twenty, thirty identical high-rise tower blocks, the now-dominant form of residential architecture about whose appearance many Westerners here express a quasi-spiritual despair. That these apateu danji don't really bother me personally has less to do with my actively liking them than with my somehow not really seeing them anymore. The architecture-and-urbanism-inclined Fouser's public position is less negatively oriented toward the tower blocks than positively oriented toward hanok, the traditional single-story courtyard houses they often replaced, at least in their first few generations of construction.

While living in Korea, Fouser somehow managed to avoid falling into the domestic media circuit, with its ever less satiable demand for Korean-speaking foreigners. Yet he became quite well-known here nevertheless, and has remained so even while living in the United States. That owes not least to his advocacy for hanok preservation, which, I gather, has not always been a universally popular cause. From what I've heard, Korean architects with an interest in hanok long faced the obstacle of an indifferent or even hostile public, who would instinctively respond with balking about maintenance or questions like "But aren't they cold?" In the second half of the century, the priority was to build housing rapidly and in sufficiently great quantities to house everyone rushing to Seoul, outfitting each generation of building more thoroughly with First-World appurtenances. (Ovens and garbage disposals, however, remain elusive.)

Now, having achieved a level of development that in places far outdoes the old First World itself, Korea has turned back to assess the value of its past: maybe as penitence for having been so eager to scrap it, maybe as a national branding exercise. The hanok (a word that just means "Korean house," as hanbok means "Korean clothing" or hanwoo means "Korean beef") has become one symbol of what I shudder to call "K-architecture." In order to experience it, a foreign tourist in Seoul might well head straight to Bukchon Hanok Village, a showcase neighborhood whose rich residents live behind gates and whose shops cater to twenty-something couples on dates. The latter have also become the very lifeblood of Ikseon-dong, a nineteen-thirties urban hanok development (in a sense, the apateu danji of its day) that became what Koreans call a "hot place" a few years ago.

I enjoy my own occasional visits to Bukchon and Ikseon-dong, but I wouldn't want to live in either of them. Nor, seemingly, did Fouser, who after purchasing and renovating a handsome urban hanok of his own did what he could to prevent its neighborhood from becoming another such combination of wealthy enclave and tourist trap — just the kind of "hot place," of course, that no few developers in Seoul would kill to build. The seriousness of this both figurative and literal investment in Korea makes Fouser's departure from the country not long thereafter somewhat difficult to understand. But then, Exploring Cities with Robert Fouser reveals its author as admirably willing to be uprooted, or to uproot himself. It could simply be that no one city can keep his interest for too long at a stretch: not even Seoul, which he describes as more of a hometown than his hometown.

Fouser also gets essays out of less obviously interesting cities: Providence, where he lived at the time of writing; Kagoshima and Kumamoto, where his students were born local and intended, for the most part, to stay local; and even Daejeon, which, though it lies less than an hour south of Seoul by KTX (Korea's answer to the Shinkansen), I visited for the first time just a few weeks ago. As with much else, Fouser got there long before me. In Japan one would describe such a figure as a sensei. Since I came to know Fouser and his work through Korea, I should call him my sonsaengnim, at least in the areas of exploring cities and learning languages. Now — inevitably, it seems — I, too, find myself writing a book in Korean, though not an urban autobiography. Maybe I'll be ready for that in a couple of decades.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His current projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.